- Back to Home »

- Why we need affirmative action

National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012): The Supreme Court upheld most of the Affordable Care Act, the Obama administration's health care reform law, on June 28, 2012. The decision determined how hundreds of millions of Americans will receive health care. Take a look at other important cases decided by the highest court in the land.

National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012): The Supreme Court upheld most of the Affordable Care Act, the Obama administration's health care reform law, on June 28, 2012. The decision determined how hundreds of millions of Americans will receive health care. Take a look at other important cases decided by the highest court in the land.  Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010): Activists rally in February 2012 to urge the Supreme Court to overturn its decision that fundamentally changed campaign finance law by allowing corporations and unions to contribute unlimited funds to political action committees not affiliated with a candidate.

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010): Activists rally in February 2012 to urge the Supreme Court to overturn its decision that fundamentally changed campaign finance law by allowing corporations and unions to contribute unlimited funds to political action committees not affiliated with a candidate.  Texas v. Johnson (1989): The Supreme Court overturned the decision that convicted Gregory Lee Johnson of desecrating a venerated object after he set an American flag on fire during a protest. The court ruled that Johnson (at right with his lawyer, William Kunstler) was protected under the First Amendment right to freedom of speech.

Texas v. Johnson (1989): The Supreme Court overturned the decision that convicted Gregory Lee Johnson of desecrating a venerated object after he set an American flag on fire during a protest. The court ruled that Johnson (at right with his lawyer, William Kunstler) was protected under the First Amendment right to freedom of speech.

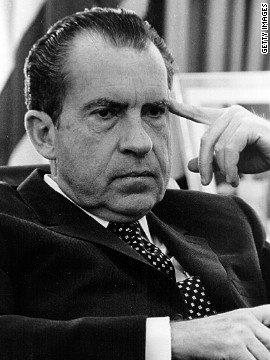

United States v. Nixon (1974): When President Richard Nixon claimed executive privilege over taped conversations regarding the Watergate scandal, the Supreme Court ruled that he had to turn over the tapes and other documents. The ruling set a precedent limiting the power of the president of the United States.

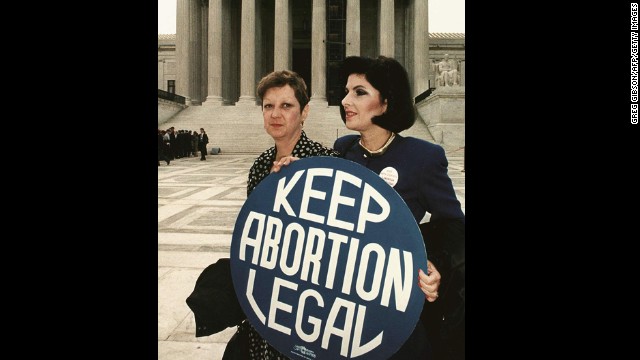

Roe v. Wade (1973): Norma McCorvey, identified as "Jane Roe," sued Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade over a law that made it a felony to have an abortion unless the life of the mother was in danger. The court agreed with Roe and overruled any laws that made abortion illegal in the first trimester. Here, McCorvey, left, stands with her attorney Gloria Allred in 1989.

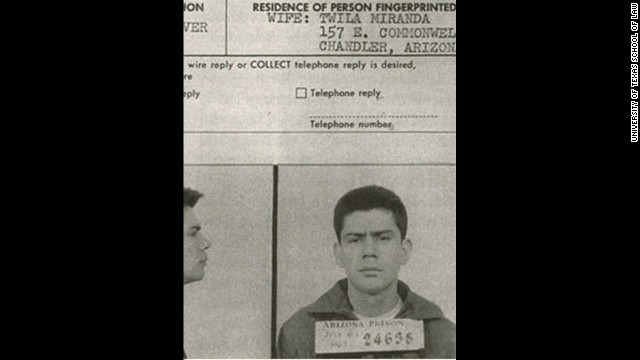

Roe v. Wade (1973): Norma McCorvey, identified as "Jane Roe," sued Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade over a law that made it a felony to have an abortion unless the life of the mother was in danger. The court agreed with Roe and overruled any laws that made abortion illegal in the first trimester. Here, McCorvey, left, stands with her attorney Gloria Allred in 1989.  Miranda v. Arizona (1966): Ernesto Miranda confessed to a crime without the police informing him of his right to an attorney or right against self-incrimination. His attorney argued in court that the confession should have been inadmissible, and in 1966, the Supreme Court agreed. The term "Miranda rights" has been used since.

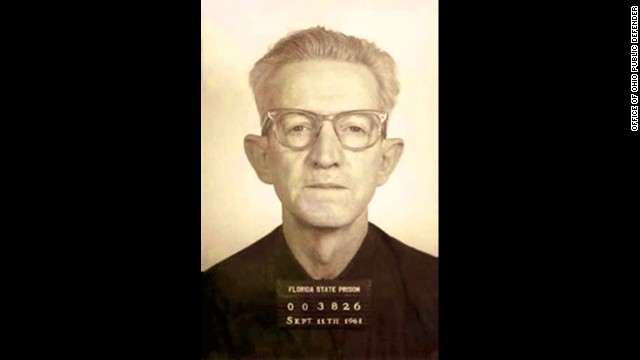

Miranda v. Arizona (1966): Ernesto Miranda confessed to a crime without the police informing him of his right to an attorney or right against self-incrimination. His attorney argued in court that the confession should have been inadmissible, and in 1966, the Supreme Court agreed. The term "Miranda rights" has been used since.  Gideon v. Wainwright (1963): The Supreme Court overturned the burglary conviction of Clarence Earl Gideon after he wrote to the court from his prison cell, explaining he was denied the right to an attorney at his 1961 trial.

Gideon v. Wainwright (1963): The Supreme Court overturned the burglary conviction of Clarence Earl Gideon after he wrote to the court from his prison cell, explaining he was denied the right to an attorney at his 1961 trial.  Mapp v. Ohio (1961): The Supreme Court overturned the conviction of Dollree Mapp because the evidence collected against her was obtained during an illegal search. The ruling re-evaluated the Fourth Amendment, which protects citizens against unreasonable searches and seizures.

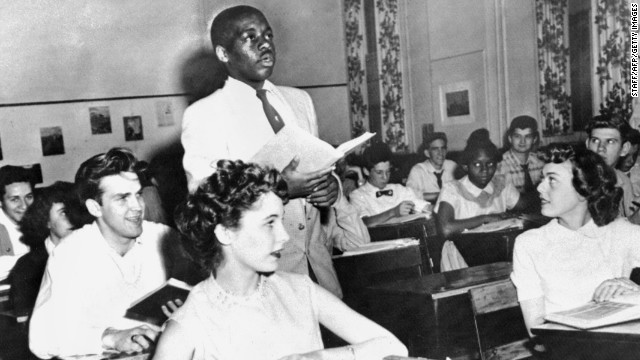

Mapp v. Ohio (1961): The Supreme Court overturned the conviction of Dollree Mapp because the evidence collected against her was obtained during an illegal search. The ruling re-evaluated the Fourth Amendment, which protects citizens against unreasonable searches and seizures.  Brown v. Board of Education (1954): Nathaniel Steward recites his lesson surrounded by white classmates at the Saint-Dominique School in Washington. In Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional to separate students based on race.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954): Nathaniel Steward recites his lesson surrounded by white classmates at the Saint-Dominique School in Washington. In Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional to separate students based on race.  Korematsu v. United States (1944): Fred Korematsu, a Japanese-American man, was arrested after authorities found out that he claimed to be a Mexican-American to avoid an internment camp during World War II. The court ruled that the rights of an individual were not as important as the need to protect the country during wartime. In 1998, President Bill Clinton awarded Korematsu the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Korematsu v. United States (1944): Fred Korematsu, a Japanese-American man, was arrested after authorities found out that he claimed to be a Mexican-American to avoid an internment camp during World War II. The court ruled that the rights of an individual were not as important as the need to protect the country during wartime. In 1998, President Bill Clinton awarded Korematsu the Presidential Medal of Freedom.  Plessy v. Ferguson (1896): Homer Plessy was arrested when he refused to leave a whites-only segregated train car, claiming he was 7/8 white and only 1/8 black. The Supreme Court ruled that "separate but equal" facilities for blacks were constitutional, which remained the rule until Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

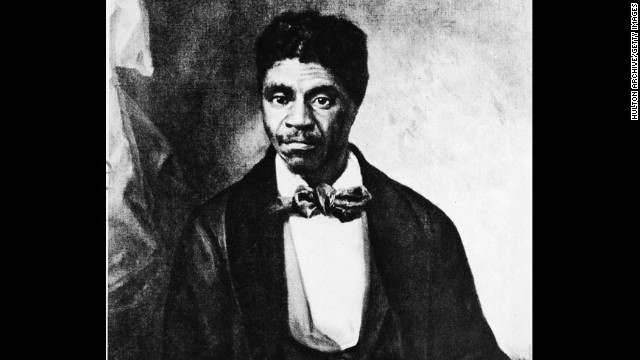

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896): Homer Plessy was arrested when he refused to leave a whites-only segregated train car, claiming he was 7/8 white and only 1/8 black. The Supreme Court ruled that "separate but equal" facilities for blacks were constitutional, which remained the rule until Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.  Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857): When Dred Scott asked a circuit court to reward him his freedom after moving to a free state, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress didn't have the right to prohibit slavery and, further, that those of African-American descent were not protected by the Constitution.

Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857): When Dred Scott asked a circuit court to reward him his freedom after moving to a free state, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress didn't have the right to prohibit slavery and, further, that those of African-American descent were not protected by the Constitution.  Gibbons v. Ogden (1824): This was the first case to establish Congress' power to regulate interstate commerce. The ruling signaled a shift in power from the states to the federal government. Aaron Ogden, seen here, was given exclusive permission from the state of New York to navigate the waters between New York and certain New Jersey ports. When Ogden brought a lawsuit against Thomas Gibbons for operating steamships in his waters, the Supreme Court sided with Gibbons.

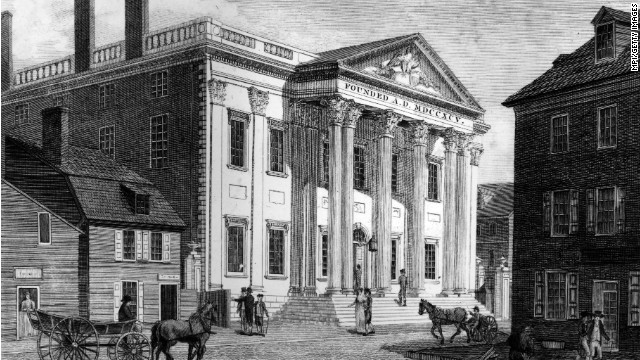

Gibbons v. Ogden (1824): This was the first case to establish Congress' power to regulate interstate commerce. The ruling signaled a shift in power from the states to the federal government. Aaron Ogden, seen here, was given exclusive permission from the state of New York to navigate the waters between New York and certain New Jersey ports. When Ogden brought a lawsuit against Thomas Gibbons for operating steamships in his waters, the Supreme Court sided with Gibbons.  McCulloch v. Maryland (1819): In response to the federal government's controversial decision to institute a national bank in the state, Maryland tried to tax the bank out of business. When a federal bank cashier, James W. McCulloch, refused to pay the taxes, the state of Maryland filed charges against him. In McCulloch v. Maryland, the Supreme Court ruled that chartering a bank was an implied power of the Constitution. The first national bank, pictured, was created by Congress in 1791 in Philadelphia.

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819): In response to the federal government's controversial decision to institute a national bank in the state, Maryland tried to tax the bank out of business. When a federal bank cashier, James W. McCulloch, refused to pay the taxes, the state of Maryland filed charges against him. In McCulloch v. Maryland, the Supreme Court ruled that chartering a bank was an implied power of the Constitution. The first national bank, pictured, was created by Congress in 1791 in Philadelphia.

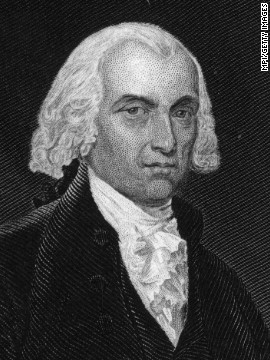

Marbury v. Madison (1803): When Secretary of State James Madison, seen here, tried to stop Federal loyalists from being appointed to judicial positions, he was sued by William Marbury. Marbury was one of former President John Adams' appointees, and the court decided that although he had a right to the position, the court couldn't enforce his appointment. The case defined the boundaries of the executive and judicial branches of government.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

- Two cases before the Supreme Court challenge longstanding policies on race

- Affirmative action and the Voting Rights Act came out of the civil rights era of the 1960s

- Julian Zelizer says despite progress in racial issues, both policies are still needed

Editor's note: Julian Zelizer is a professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University. He is the author of "Jimmy Carter" and "Governing America."

(CNN) -- The Supreme Court is expected to issue a number of historic decisions in the coming weeks about how the government deals with race issues.

With the Voting Rights Act and affirmative action on the agenda, the nation is watching closely to see what the highest court will say.

The court is tackling affirmative action through a case involving the University of Texas and a student who was denied admission. With the Voting Rights Act, the court is looking again at the law, including Section 5, which stipulates that some jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination are required to submit changes in districting and voting laws for clearance.

Both issues came out of the 1960s, one under President Lyndon Johnson in 1965 and another under President Richard Nixon in 1969, with the intention of helping to correct more than a century of racial inequality.

In 1965, in the wake of massive grassroots protests, Congress passed the historic legislation that ensured the federal government would protect the right of African Americans to freely participate in the vote. Johnson responded to immense pressure that came from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and civil rights protesters, who put themselves on the line and suffered violence to obtain this right.

In 1969, the Department of Labor launched the Philadelphia Plan, requiring unions involved in projects receiving federal funds to hire a percentage of African Americans in proportion to the composition of the local population. Nixon supported this plan as much for politics as policy. His goal was to divide the Democratic coalition by pitting African Americans against organized labor.

The goal of both programs, though born for very different political reasons, was for the government to proactively tackle problems that aggravated racial equality. Johnson's speech in 1965 laid out the rationale.

Sonia Sotomayor: I was an alien

Sonia Sotomayor: I was an alien  Affirmative action case in court's hands

Affirmative action case in court's hands In a powerful address at Howard University, he said: "You do not wipe away the scars of centuries by saying: Now you are free to go where you want, and do as you desire, and choose the leaders you please. You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, 'you are free to compete with all the others," and still justly believe that you have been completely fair."

These programs have been controversial from the start.

As the late historian Hugh Davis Graham argued with regards to affirmative action, they moved away from the idea that the government would guarantee individual rights after they had been violated toward establishing policies whereby the government would take steps to ensure that racist practices would not even be allowed to occur. The goal, though more controversial, was to take stronger steps to design institutions that would not perpetuate racism.

During the late 1960s, some members of the Nixon administration tried to push for changes to the Voting Rights Act that would have severely weakened the legislation, including dismantling the clearance provision that required governments holding elections to gain approval from the Justice Department to any changes in their voting process. But the supporters pushed back, and the laws remained intact.

There have been repeated challenges to the Voting Rights Act and affirmative action, especially as it was extended into areas other than employment, such as education, but they have failed.

This time the threat seems greater than before. The efforts of conservatives to transform the composition of the federal courts in a rightward direction are finally starting to pay off. For the first time, many experts feel the conservatives have the numbers they need to make substantial changes in both of these laws.

The decisions will have huge ramifications. If the court begins to knock down these two pillars of civil rights policies, they would set back the government's power to deal with racial problems.

These programs have been a stunning success, slowly starting to repair the immense damage caused by the nation's history of racism. The Voting Rights Act produced big increases in the number of African Americans voting and produced several generations of African American elected officials.

Affirmative action has helped bolster the African American middle class and opened access to institutions from education to employment.

To be sure, there are legitimate questions that have been raised about both of these programs, areas where they certainly could be strengthened. Experts have debated how affirmative action programs could do a better job, particularly by putting emphasis on giving those who suffer from class-based discrimination more access to higher education rather than relying solely on race as a standard. But improving and strengthening programs is different than knocking them down.

If the court makes the decision to turn back the clock on these two policies, it would be a huge setback for the civil rights movement that changed the nation 50 years ago. Even with all the progress we've seen, the court must be cautious before weakening programs that respond to the many racial challenges that still need to be fixed, as well as to new ones that have emerged.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Julian Zelizer.