- Back to Home »

- 50+ years, zero executions

The U.S. military has not executed one of its own since 1961. Here are the five men on the military's death row.

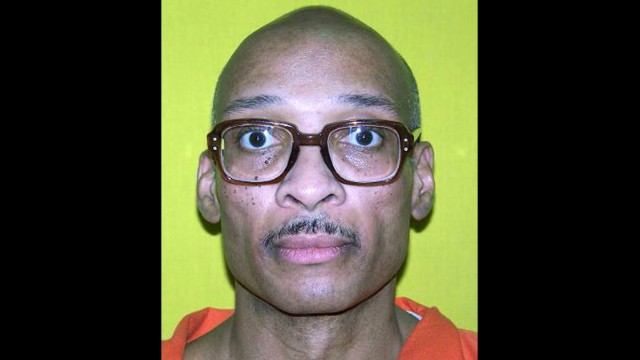

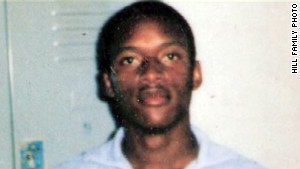

The U.S. military has not executed one of its own since 1961. Here are the five men on the military's death row.  Former Pvt. Ronald Gray has been on death row since 1988. A court-martial panel unanimously convicted him of committing two murders and other crimes in the Fayetteville, North Carolina, area. Gray, who is the longest serving inmate on the military's death row, was granted a temporary stay of execution by a U.S. district court in 2008.

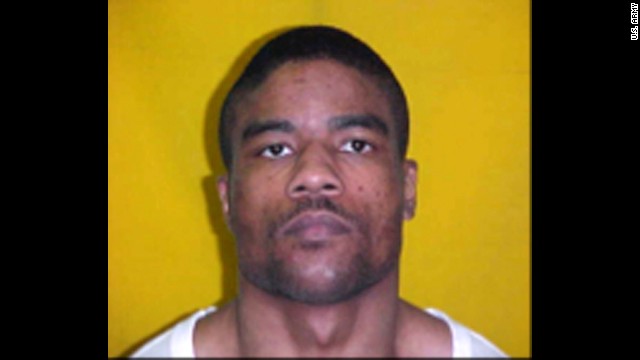

Former Pvt. Ronald Gray has been on death row since 1988. A court-martial panel unanimously convicted him of committing two murders and other crimes in the Fayetteville, North Carolina, area. Gray, who is the longest serving inmate on the military's death row, was granted a temporary stay of execution by a U.S. district court in 2008.  Former Army Pfc. Dwight J. Loving was sent to death row in 1989 after being convicted in the December 1988 killings of two taxi drivers -- one a retired Army sergeant, the other a soldier moonlighting to make extra money. Loving, who was stationed at Fort Hood, Texas, gave what observers say is an "undisputed" videotaped confession.

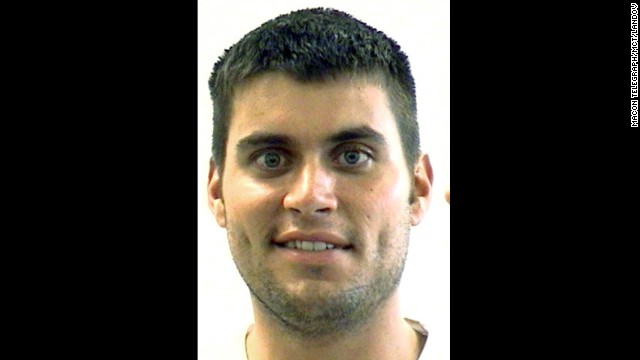

Former Army Pfc. Dwight J. Loving was sent to death row in 1989 after being convicted in the December 1988 killings of two taxi drivers -- one a retired Army sergeant, the other a soldier moonlighting to make extra money. Loving, who was stationed at Fort Hood, Texas, gave what observers say is an "undisputed" videotaped confession.  Former Army Sgt. Hasan Akbar was handed a death sentence for killing two soldiers and wounding 14 others at Camp Pennsylvania, Kuwait, during the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. On March 23, 2003, Akbar threw four hand grenades into tents where soldiers were sleeping and then opened fire on other soldiers.

Former Army Sgt. Hasan Akbar was handed a death sentence for killing two soldiers and wounding 14 others at Camp Pennsylvania, Kuwait, during the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. On March 23, 2003, Akbar threw four hand grenades into tents where soldiers were sleeping and then opened fire on other soldiers.  Former Air Force Sr. Airman Andrew Witt was sent to death row in 2005 after a military jury found him guilty in the premeditated stabbing deaths of an airman and his wife on July 5, 2004. Witt, the only Air Force service member on death row, was also found guilty in the attempted murder another airman.

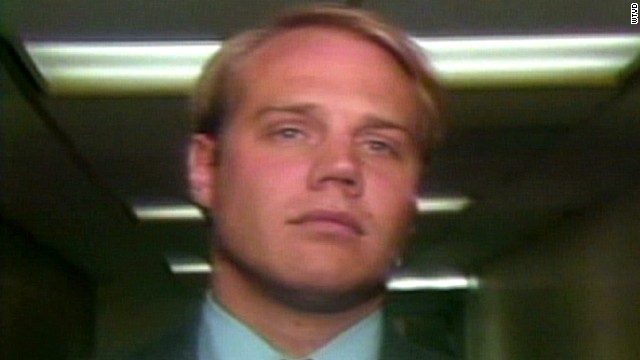

Former Air Force Sr. Airman Andrew Witt was sent to death row in 2005 after a military jury found him guilty in the premeditated stabbing deaths of an airman and his wife on July 5, 2004. Witt, the only Air Force service member on death row, was also found guilty in the attempted murder another airman.  Former Army Master Sgt. Timothy Hennis was sentenced to death in 2010 for the May 1985 killings of a woman and her two young daughters in Fayetteville, North Carolina. The case gained widespread notoriety and became the subject of a book and a television miniseries. Hennis was initially convicted of the killings in 1986 in state court and spent two years on death row before the case was overturned. He was acquitted at a second trial in 1989. In 2006, improved DNA testing linked Hennis to the killings. The military tried Hennis because he couldn't be tried in a state court for a crime for which he had previously been acquitted.

Former Army Master Sgt. Timothy Hennis was sentenced to death in 2010 for the May 1985 killings of a woman and her two young daughters in Fayetteville, North Carolina. The case gained widespread notoriety and became the subject of a book and a television miniseries. Hennis was initially convicted of the killings in 1986 in state court and spent two years on death row before the case was overturned. He was acquitted at a second trial in 1989. In 2006, improved DNA testing linked Hennis to the killings. The military tried Hennis because he couldn't be tried in a state court for a crime for which he had previously been acquitted. - Five men are on the military's death row

- Military has not executed anyone since 1961

- Of 16 capital punishment verdicts since 1984, 11 have been overturned

- Army Maj. Nidal Hasan could become the next resident of military death row

(CNN) -- Ronald Gray raped and battered at least seven women. He killed four, and left the others for dead -- the bodies dumped around Fort Bragg and the neighboring city of Fayetteville, North Carolina, between 1986 and 1987.

He was caught and, just as in the civilian system, he was tried.

He was found guilty by a jury of his peers, just as in the civilian system.

And a death sentence was passed, just as would have been possible in a civilian court for such a heinous crime.

But when it comes to staying alive, history is on Gray's side. The U.S. military has not executed one of its own since 1961.

The former soldier came close to being put to death in 2008, when then President George W. Bush signed a warrant authorizing Gray's execution -- a requirement for capital punishment in the military.

Hasan's defense: Protecting Taliban

Hasan's defense: Protecting Taliban  Toobin: Hasan wants suicide by judge

Toobin: Hasan wants suicide by judge  Ft. Hood suspect paid $280k since 2009

Ft. Hood suspect paid $280k since 2009  President to Pentagon: Stop sexual abuse

President to Pentagon: Stop sexual abuse A federal court gave Gray a last-minute temporary stay, and today he -- along with four other former servicemen -- remains on the military's death row at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

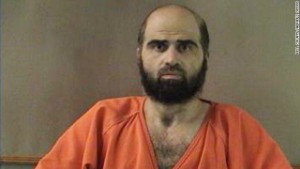

Army Maj. Nidal Hasan may become the next resident of the military's death row, if he is convicted for the shooting rampage at Fort Hood that killed 13 people and sentenced to death. Opening statements in the murder trial are scheduled to begin August 6.

Legal issues, including whether cases were handled appropriately, have affected some cases, analysts say.

A look at the last U.S. soldier executed by the military

But a larger part of the equation appears to be the sometimes cloistered military culture, from a commanding general who can override a jury's verdict to the routine military reshuffling of personnel, including prosecutors, defense attorneys and witnesses, every two or three years.

"The military is a community of solidarity, a brotherhood and sisterhood, all to its own," defense lawyer Teresa Norris said. "There is a real reluctance to execute fellow soldiers unless it's absolutely the worst kind of case and this is the only way."

There is little disagreement by the Army that the death penalty is used only in extreme cases. But that doesn't mean it won't mete out or carry out the punishment, it says.

"Adherence to the law, due process, and respect for the rights of someone accused of crime, combined with respect for civilian oversight of the military justice system, should not be mistaken for an unwillingness to execute the law," said Army Lt. Col. S. Justin Platt, deputy chief of public affairs.

Military terror convictions to get high-profile judicial review

'The Castle'

Norris represents former Army Pfc. Dwight Loving, sentenced to death in 1989 when he was 21 years old for robbing and murdering two cab drivers -- a retired sergeant and a soldier moonlighting to earn extra money -- at Fort Hood, Texas.

Sent to an intimidating prison with a brick façade at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Loving for a time was expected to be the first person the military put to death in decades.

Military officers and other important types were shown where he was kept in the stark prison known as "the Castle," reserved for the worst of the worst and the inspiration for a book and later a movie, "The Last Castle," starring Robert Redford as a court-martialed general.

They were told, Norris says, that Loving would soon be executed.

That was 1992.

Today, "the Castle" has been rendered obsolete, and Loving is awaiting execution in a new, state-of-the-art military prison.

"Me and my client were essentially expecting an execution within 18 months, and here we are all these years later," said Norris, who represented Loving as a military defense attorney and now as a civilian.

Executing troops

The U.S. military has executed 135 men since 1916 -- considered the start of the era of the modern fighting force -- for crimes ranging from murder to rape, according to the non-profit Death Penalty Information Center in Washington, D.C.

Soldier investigated for sexual assault

Soldier investigated for sexual assault  Florida bill would speed up executions

Florida bill would speed up executions  Execution halted at the last moment

Execution halted at the last moment  Plea in Afghan massacre

Plea in Afghan massacre Only 10 of these executions have taken place since 1951. The U.S. military carried out its last execution on April 13, 1961, with the hanging of Army Pvt. John A. Bennett, who was convicted in 1955 of the rape and attempted murder of an 11-year-old Austrian girl.

A number of death sentences were converted to life sentences in 1983 when a military appeals court found the death penalty was unconstitutional because of problems with the armed forces' sentencing guidelines.

A year later, President Ronald Reagan reinstated capital punishment in the military. Of the 16 people sent to the military's death row since 1984, 11 have had their sentences overturned. Two of those decisions were taken by commanding generals. The other nine cases were overturned by military appeals courts over various questions about the application of law.

Unlike in civilian courts where prosecutors decide charges, a commanding general -- who has other duties -- decides whether a military defendant will face the death penalty. That general also can reduce a sentence.

It's one of the biggest differences with the civilian system and it leads to one of the major criticisms of the decentralized nature of the military judicial system, where each branch operates independently.

"Even if you have two identical cases, one being prosecuted by one commander at one base and other being prosecuted by a commander at another base, you may have different outcomes because the commanders may have different philosophies," said Dwight Sullivan, a former Marine prosecutor and judge who now works as a civilian attorney specializing in military death penalty appeals.

Such was the case with Curtis Allen Gibbs, a Marine who was sentenced to death in 1990 for killing and nearly decapitating a woman with a sword near Camp Lejeune.

A jury returned a sentence of death for Gibbs, but a commanding general overturned the decision and gave him life. At the time, the general cited a reluctance to authorize the execution of a service member during a military conflict -- the Persian Gulf War, according to published accounts.

"He didn't want to impose the death penalty, and it struck me as strange because the jury had heard and evaluated all the evidence and decided that's what he should get," said Guy Womack, a retired Marine prosecutor who helmed the Gibbs case.

As a result, Womack believes the problem lies not with military juries but rather with what follows: the commanding general and the appeals process.

Once the death penalty has been handed down, an appeal is automatic and eventually reviewed by the military's top court, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces -- even if the service member doesn't want it.

"It's a very slow process, and I don't think they like the idea of confirming the death penalty," said Womack, who now works as a civilian attorney who specializes in defending military clients.

Today, the death sentences of all five men on the military's death row are either on appeal or under legal review.

"The process by which legal matters in the military are adjudicated are taken extraordinarily seriously by a professional panel of peers that weigh all matters and due consideration at their due course," said Army Lt. Col. Todd Breasseale, a Pentagon spokesman.

Military chiefs oppose removing commanders from sexual assault probes

Fewer cases

If the Gulf War affected the Gibbs case, it may also have had a wider impact.

The 1990-1991 conflict was the first major deployment of U.S. troops since Vietnam and may have made the military switch its focus, says Catherine Grosso, who co-authored a study that examined the military death penalty system.

She found fewer death penalty cases brought by the military in recent decades.

"The important break point in the study is 1990," she said.

Grosso did not come to conclusions for why this happened in her study, which addressed racial questions.

But she told CNN that while legal changes in 1997 could have played a role by adding the option of a sentence of life without the possibility of parole, it doesn't explain the drop in death penalty prosecutions before 1997.

That's where the buildup to and fighting of the Gulf War, from 1990-1991 may have played a role.

"Maybe that made the military focus in a different way," she said.

But Eugene Fidell, a former judge advocate who teaches military justice at Yale Law School, said there is "insufficient data to draw a broad conclusion."

"Anyone who commits multiple murders is a viable candidate for a capital prosecution, regardless of the setting," he said. "The more victims, the likelier."

Present day

Army Staff Sgt. Robert Bales pleaded guilty last month to avoid the death penalty for killing 16 Afghan civilians in Kandahar in March 2012.

Most legal experts agree the case against Nidal Hasan, the Army psychiatrist accused of opening fire in 2009 at a deployment center at Fort Hood, will be tough to overcome -- given the evidence.

"This is broad daylight, multiple assaults before witnesses on a base," Fidell said. "As capital cases go, this is an easy one."

But whether a jury hands down a death sentence remains to be seen.

And whether any death sentence is carried out is even more at question.

Hagel orders review of military judicial authority