- Back to Home »

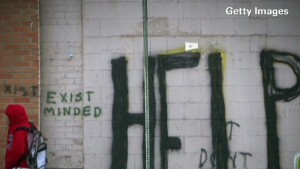

- Detroit, the 'used to be' city

- Heidi Ewing: People in Detroit always talk about how pretty, how lively, things used to be

- Ewing grew up in suburbs, but she loved the snapshots of her parents in 1960s Detroit

- She wanted to film the "comeback city," but found desperate people on the margins

- Ewing decided to turn camera on the folks who stayed to bring Detroit back to its vibrant past

Editor's note: Heidi Ewing is an Academy Award-nominated filmmaker, the owner of Loki Films and the co-director of "Detropia," a new documentary about Detroit and its uncertain future. She is from Metro Detroit and lives in New York. On Twitter, follow Ewing @HeidiLoki and "Detropia" @detropiathefilm.

(CNN) -- "This block used to be full of pretty little houses with well-kept yards." When you spend any time in the newly bankrupt Detroit, you get very accustomed to hearing the words "used to be."

It's a phrase often uttered by the old-timer looking fly in the red suit and crocodile shoes, who may actually remember when Detroit was the pinnacle of industry. But it's also said liberally by young men and women who have been hearing about Detroit's good old days from their parents and grandparents. The thing is, when you are in or around Detroit for awhile, "used to be" seeps into your brain through osmosis -- a simultaneously fuzzy and vivid collective memory that makes the Motor City the most nostalgic place in America.

My parents grew up in Detroit and, like too many others, fled to the suburbs in 1967 after years of lingering racial tension boiled over and riots rocked the city. That meant that my sister, brother and I grew up 20 minutes from Detroit's 8 Mile, the border that, like a hammer, separates the current and "ex" Detroiters.

My grandma stayed stubbornly behind on Faust Street on the Northwest side of Detroit. I would visit on weekends and go through the attic, looking for clues of what Detroit used to be.

I especially relished the boxes of black and white snapshots of my parents in the 1960s. There they were in one shot, sipping cheap Cold Duck sparkling wine while throwing a party at La Plaisance, their high-rise in Lafayette Park, a sweet pad that overlooked the Stroh's brewery.

In another one of my favorites, they stand with my older brother PJ, then 3 years old, in front of J.L. Hudson's, the beloved department store where the elevators had operators and the restaurant served salads with celery seed dressing. It was hard not to be curious and a bit envious of this city life that had eluded my siblings and me.

In high school, my girlfriends and I made pilgrimages past 8 Mile Road every weekend to hang out with the city boys who went to the excellent U. of D. Jesuit High. They introduced us to Rock n' Bowl, a bowling alley that blasted New Order and let us drink the Mad Dog 20/20 we had bought illegally from a liquor store with bulletproof glass. The city felt dangerous, but we felt immortal.

I finally got my chance to live in Detroit in 2010, when I moved there to make a documentary about the city. Like many Americans, I had caught a whiff of optimism from Detroit, rumors about newcomers and artists descending on "The D," news of urban planners and visionaries who had a plan to make it the city of the future. So I came with my crew, ready to roll, even an uplifting title in mind: "Detroit Hustles Harder."

But finding the easy comeback story proved challenging. Although we did indeed encounter a small gang of young creative types and revitalization efforts inside Detroit's small Midtown area, beyond these few blocks of hope we found a citizenry fending entirely for itself.

Albom: Detroit is not Atlantis

Albom: Detroit is not Atlantis  Detroit files for bankruptcy

Detroit files for bankruptcy  Detroit's fall from grace

Detroit's fall from grace The truth is, we encountered an endless parade of grotesquerie in Detroit: A scary dude named Jay Thunderbolt, face disfigured from a gunshot, running a depraved strip club out of his deceased parents' home. A young man named Chuck trying to make it as an R&B artist when his house gets shot up by men with AK 47s on Christmas Eve, his calls to the Detroit Police unanswered. An old woman, head of a community cleanup group, robbed in her home in broad daylight. Illegal "scrappers" dismantling an old Cadillac repair shop just to get money for beer. An overworked demolition crew, hired by the city, brimming with tales of finding frozen bodies during routine jobs.

We were flummoxed. Was our truth-telling becoming an exercise in exploitation? Where were the solutions we came for? It was time to stop asking who may save Detroit and instead ask Detroiters what compelled them to stay in this dysfunctional place.

We started with Tommy Stephens, a former schoolteacher who, despite thinning crowds, opens the Raven Lounge every weekend on a bombed-out block in East Detroit. He stays because "Detroit without a black-owned blues club just isn't Detroit anymore. And somebody's got to do it."

Along Michigan Avenue, we met George, who, after 30 years still slogs away at UAW Local 22, trying, often in vain, to keep jobs in the city. "The middle class was born right here in Detroit," he said. And across town, there was David, who turned down an easy life in California to run the Detroit Opera House. "If a city has no cultural institutions," he said, "then is it still a city at all?"

All these people had one thing in common: A deep sense of duty and unflagging belief that they need to do their part to preserve some of what had made Detroit a source of great pride for this country. With looming slashes to pensions and the threat of more service cutbacks that will come with Chapter 9, I wonder how many loyalists will question their sacrifices?

The subjects of the film, which in the end we called "Detropia," could not escape the deep nostalgia that compels them to stick with Detroit. This burden of the past haunts even the 20-something Crystal Starr, who spends her time off prowling through abandoned buildings, flashlight in one hand and a book about Detroit's history in the other.

She'd climb to the top floors and sit in old kitchens, looking out the giant windows, panes long gone, trying to recall a time when this place was on the rise. "It's weird," she said one day, looking out at the cityscape. "I wasn't even here for the good times, but still, I have the memory of this place when it was bangin'."

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Heidi Ewing.