- Back to Home »

- How 'superwind' blows away stars

- Meg Urry: New data have mapped a "superwind" flowing out of a nearby galaxy

- Urry: There is enough mass in the wind to carry away a lot of gas in the galaxy

- She says this suggests an answer to why galaxies today do not have more stars

- Urry: It's because cold gas, which forms stars, is being blown out of galaxies

Editor's note: Meg Urry is the Israel Munson professor of physics and astronomy at Yale University and director of the Yale Center for Astronomy and Astrophysics.

(CNN) -- We know the devastating force of Class 5 hurricanes, which have sustained winds exceeding 156 miles per hour (or 70 meters per second), like Hurricane Katrina.

Now, imagine winds that are 2,000 times faster, stripping a galaxy of its future light and heat. Devastating doesn't begin to describe it.

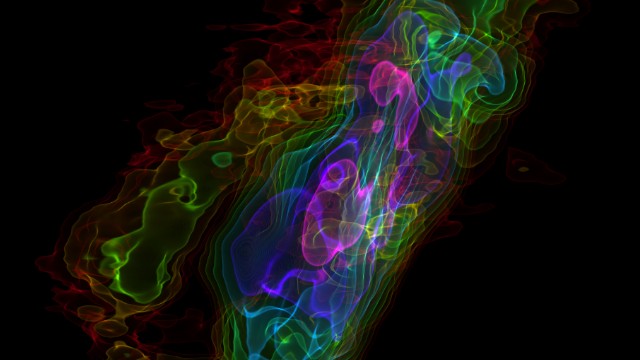

Data from the new Atacama Large Millimeter Array, a growing array of radio telescopes in the high desert of Chile, have mapped a "superwind" flowing out of a nearby galaxy.

This galaxy, named NGC 253 (because it is the 253rd object in the New General Catalog of galaxies), is a bit like our own Milky Way galaxy in that it has a large disk of cold gas (atoms and molecules of matter) out of which stars are constantly forming.

But NGC 253 is a galaxy on steroids: It is forming stars at about 100 times the rate of the Milky Way. That's why it's called a "starburst" galaxy. This made it a great target to observe with ALMA, which can see light from the gas from which those stars form.

This light is not visible with the human eye. It's electromagnetic radiation like visible light but with a much longer wavelength. To observe it, we use radio telescopes, which look a lot like your basic satellite dish, only much bigger and more numerous. (Eventually, ALMA will consist of 66 dishes, each 40 feet in diameter.)

Astronomers used ALMA to measure the amount of carbon monoxide molecules in NGC 253's superwind and to extrapolate the total amount of cold gas being blasted out of the galaxy.

What's the big deal? Well, for the first time, the new ALMA analysis shows enough mass in this wind to carry away a large fraction of the gas in the galaxy. This suggests an answer to a longstanding mystery about why galaxies today do not have more stars.

Let's delve more into this mystery by looking at galaxies grow. Over the 13.7 billion years since the Big Bang origin of the universe, familiar building blocks of matter -- electrons, protons and neutrons -- cooled and combined to form atoms. Then, as this gas cooled further, some of the atoms combined to form molecules. Meanwhile, gravity amplified regions of high density so stars and whole galaxies formed out of the cold, dense gas.

But straightforward calculations describing this process tell us that today's galaxies should be filled with more stars, shining more brightly, than we see. Something must disrupt the ordinary, gravity-powered process of coalescence and star formation.

What's missing? Cold gas.

The new ALMA data show clearly that the gas from which those stars would form is being blown out of the galaxy. It's a funny kind of death by excess: The very high number of stars forming in NGC 253 generates a lot of heat, blowing winds off their surfaces, and these streams of heated stellar material unite to push away the surrounding gas that has not formed stars.

When a superwind disrupts the gas clouds that might have formed more stars, we call it "feedback," because if the star formation rate is very high, the superwind is strong, so a lot of gas is heated and/or ejected from the galaxy, so fewer stars form, and the superwind dies down. Conspicuous over-producers like NGC 253 are doomed, it seems, to cut off their own star production.

Think of it as appetite control. Gravity has none. Gravity just keeps pulling on mass (particles, atoms, molecules, dark matter). If gravity were the only important effect, the clouds of gas would keep condensing and forming many more stars than we see. But the superwind keeps this from happening.

Alberto Bolatto of the University of Maryland, who led the ALMA study of NGC 253, explained, "For the first time, we can clearly see massive concentrations of cold molecular gas being jettisoned by expanding shells of intense pressure created by young stars. The amount of gas we measure gives us very convincing evidence that some growing galaxies blow out more gas than they take in, slowing star formation down to a crawl."

A talented science team was behind this result. But it wouldn't have been possible without the new ALMA telescope array, which was built by the U.S. National Science Foundation in partnership with Europe, Japan, Canada, Taiwan and the host country, Chile.

ALMA is the largest ground-based astronomical project ever, taking more than 20 years from conception to operation and costing about $1.3 billion, with roughly one-third funded by the National Science Foundation. It is a model of international cooperation: Each partner supplied a share of the antennas, and an international organization oversees telescope operations.

ALMA is sited in Chile because the Atacama Desert is ideal for millimeter astronomy. Its extreme dryness and high altitude -- about 16,500 feet above sea level -- mean greater atmospheric transparency to the high-frequency radio waves ALMA was designed to detect. (The wavelength of this light is about 1 millimeter, hence the "M" in the name.)

People often debate the value of astronomy. It won't cure cancer or eradicate poverty. But it has its practical value, well beyond the primary goal of understanding how the present-day universe -- and our Earth, Solar System and Milky Way galaxy -- came to be.

Astronomy pushes technology advancement. Those digital images you take with your camera or phone are possible because of tools that were developed for astronomy about 30 years ago.

Think we need a work force better trained in science and technology? Astronomy gets kids -- and the curious inner kid in all of us -- interested in science. In Chile, astronomy is an important part of the high-tech economy.

Could we live without knowing about the superwind in NGC 253? Sure. But, like art, astronomy is part of what enriches our lives. For some of us, learning where we came from is what it's all about.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Meg Urry.