- Back to Home »

- How not to be a scary stage parent

Whether it's soccer matches or beauty pageants like this one in Norwich, England, parents can become highly invested in their children's performance-based success. Click through the gallery to view stage parents and their famous offspring.

Whether it's soccer matches or beauty pageants like this one in Norwich, England, parents can become highly invested in their children's performance-based success. Click through the gallery to view stage parents and their famous offspring.  Shirley Temple celebrates her birthday in 1936 with her mother, Gertrude Temple. Her mother, recognizing her daughter's "it" factor, enrolled Shirley in dance classes at age 3. She landed her first film contract at the same age, and soon became one of the earliest and most successful child stars. The actress, now 85, went on to become a U.S. diplomat for the United Nations.

Shirley Temple celebrates her birthday in 1936 with her mother, Gertrude Temple. Her mother, recognizing her daughter's "it" factor, enrolled Shirley in dance classes at age 3. She landed her first film contract at the same age, and soon became one of the earliest and most successful child stars. The actress, now 85, went on to become a U.S. diplomat for the United Nations.  Khloe Kardashian Odom, Kylie Jenner, Kris Jenner, Kourtney Kardashian, Kim Kardashian and Kendall Jenner pose on the red carpet in 2011. The matriarch of the "Keeping Up with the Kardashians" clan manages the careers of her six children (her son, Rob Kardashian, is not pictured) and her "momagerial ways" are often a point of contention in their reality show.

Khloe Kardashian Odom, Kylie Jenner, Kris Jenner, Kourtney Kardashian, Kim Kardashian and Kendall Jenner pose on the red carpet in 2011. The matriarch of the "Keeping Up with the Kardashians" clan manages the careers of her six children (her son, Rob Kardashian, is not pictured) and her "momagerial ways" are often a point of contention in their reality show.  Lindsay Lohan, seen here with her sister Ali Lohan and mother, Dina Lohan, has had her fair share of troubles -- both legal and parental -- since she burst onto the scene in the 1998 remake of "The Parent Trap." Her parents, Michael and Dina Lohan, signed her with Ford Models when she was 3 years old. Since then, she has had various headline-making disputes with both her parents, including a fight with her mom in 2012 that ultimately resulted in a call to the police.

Lindsay Lohan, seen here with her sister Ali Lohan and mother, Dina Lohan, has had her fair share of troubles -- both legal and parental -- since she burst onto the scene in the 1998 remake of "The Parent Trap." Her parents, Michael and Dina Lohan, signed her with Ford Models when she was 3 years old. Since then, she has had various headline-making disputes with both her parents, including a fight with her mom in 2012 that ultimately resulted in a call to the police.  Jermaine, Janet, Jackie, Tito and father Joe Jackson attend a Hollywood parade in 1977. Joe, the talent manager and father of 10, was often described as a strict disciplinarian and abuse allegations have come to light in recent years. "I'm glad I was tough, because look what I came out with. I came out with some kids that everybody loved all over the world. And they treated everybody right," Jackson told CNN's Piers Morgan in a recent interview.

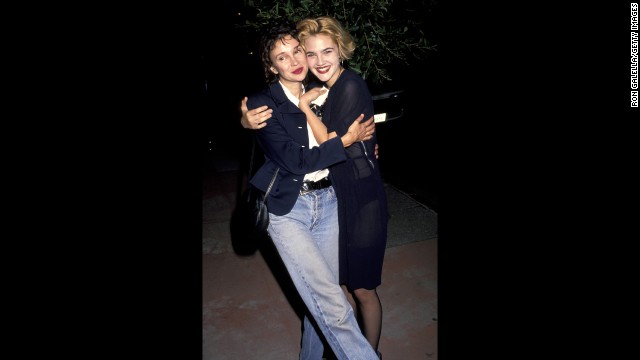

Jermaine, Janet, Jackie, Tito and father Joe Jackson attend a Hollywood parade in 1977. Joe, the talent manager and father of 10, was often described as a strict disciplinarian and abuse allegations have come to light in recent years. "I'm glad I was tough, because look what I came out with. I came out with some kids that everybody loved all over the world. And they treated everybody right," Jackson told CNN's Piers Morgan in a recent interview.  Drew Barrymore hugs her mom, Jaid Barrymore, in 1991. Drew was 6 years old when she starred as Gertie in Steven Spielberg's "E.T." With early fame came misfortune: Drew had her first drink when she was 9 and went to rehab at 13. She was granted legal emancipation from her parents when she was 15, after citing her mother as a bad influence.

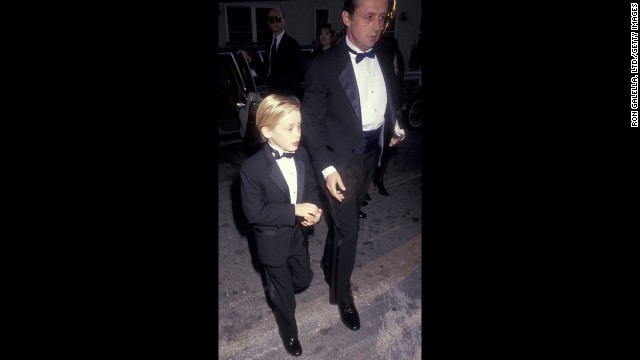

Drew Barrymore hugs her mom, Jaid Barrymore, in 1991. Drew was 6 years old when she starred as Gertie in Steven Spielberg's "E.T." With early fame came misfortune: Drew had her first drink when she was 9 and went to rehab at 13. She was granted legal emancipation from her parents when she was 15, after citing her mother as a bad influence.  Macaulay Culkin and father Kit Culkin arrive at the 17th Annual People's Choice Awards in 1993. At 16, the "Home Alone" star filed for and won emancipation from his parents, accusing them of financial mismanagement.

Macaulay Culkin and father Kit Culkin arrive at the 17th Annual People's Choice Awards in 1993. At 16, the "Home Alone" star filed for and won emancipation from his parents, accusing them of financial mismanagement.  Miley Cyrus and Billy Ray Cyrus perform "Ready, Set, Don't Go" during the 2008 CMT Music Awards. Miley became a tween sensation with her hit Disney Channel show "Hannah Montana," where her real dad starred alongside her as her fictional dad. Billy Ray has since opened up about the strain the family endured because of showbiz. "I hate to say it, but yes ... I'd take it back in a second," he told GQ in 2011.

Miley Cyrus and Billy Ray Cyrus perform "Ready, Set, Don't Go" during the 2008 CMT Music Awards. Miley became a tween sensation with her hit Disney Channel show "Hannah Montana," where her real dad starred alongside her as her fictional dad. Billy Ray has since opened up about the strain the family endured because of showbiz. "I hate to say it, but yes ... I'd take it back in a second," he told GQ in 2011.  Actress Elizabeth Taylor is seen with her mother, Sara Taylor, at the Savoy Hotel in 1982. Sara, a former stage actress herself, is often credited as the driving force behind Elizabeth's early career; she's also been criticized for being jealous of her daughter's silver screen success. "We're very much alike. We both had horrible childhoods. Well, working at the age of 9 is not a childhood," Elizabeth told CNN's Larry King of her friendship with Michael Jackson in 2006.

Actress Elizabeth Taylor is seen with her mother, Sara Taylor, at the Savoy Hotel in 1982. Sara, a former stage actress herself, is often credited as the driving force behind Elizabeth's early career; she's also been criticized for being jealous of her daughter's silver screen success. "We're very much alike. We both had horrible childhoods. Well, working at the age of 9 is not a childhood," Elizabeth told CNN's Larry King of her friendship with Michael Jackson in 2006.  Singer Justin Bieber and his mother, Pattie Mallette, share a hug at the American Music Awards. Mallette released a book in 2012 titled "Nowhere but Up: The Story of Justin Bieber's Mom" that chronicled her rise from being a teen mom with drug and alcohol addiction.

Singer Justin Bieber and his mother, Pattie Mallette, share a hug at the American Music Awards. Mallette released a book in 2012 titled "Nowhere but Up: The Story of Justin Bieber's Mom" that chronicled her rise from being a teen mom with drug and alcohol addiction.  Jessica and Ashlee Simpson pose with their parents, Joe and Tina Simpson. Joe, who became better known as "Papa Joe" to fans of Jessica's former reality show "Newlyweds," has managed both his daughters. Joe and Tina finalized their divorce in April 2013 after 34 years of marriage.

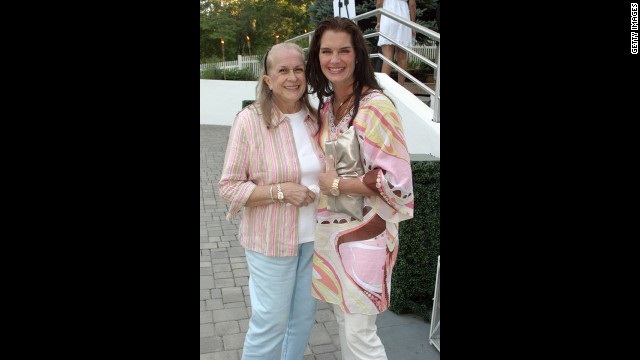

Jessica and Ashlee Simpson pose with their parents, Joe and Tina Simpson. Joe, who became better known as "Papa Joe" to fans of Jessica's former reality show "Newlyweds," has managed both his daughters. Joe and Tina finalized their divorce in April 2013 after 34 years of marriage.  Brooke Shields attends a magazine party with her mother, Teri Shields, in 2007. Teri was blasted for allowing Brooke to play a child prostitute in the 1978 film "Pretty Baby" when she was 15 years old. Teri passed away in 2012 at age 79.

Brooke Shields attends a magazine party with her mother, Teri Shields, in 2007. Teri was blasted for allowing Brooke to play a child prostitute in the 1978 film "Pretty Baby" when she was 15 years old. Teri passed away in 2012 at age 79.  Nick, Joe and Kevin Jonas, better known as the Jonas Brothers, attend the 2009 Grammy Awards with their mother, Denise Jonas. Denise often makes guest appearances on Kevin's E! reality show "Married to Jonas."

Nick, Joe and Kevin Jonas, better known as the Jonas Brothers, attend the 2009 Grammy Awards with their mother, Denise Jonas. Denise often makes guest appearances on Kevin's E! reality show "Married to Jonas."

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

- A study says stage parents may be piling their unfulfilled ambition on their children

- Performance-oriented parents can run the risk of alienating children with pressure

- Learning to stick with something is an important lesson for kids, an expert says

- But it's important to allow children to make decisions for themselves at some point

Kelly Wallace is CNN's new digital correspondent and editor-at-large covering family, career and life. She's a mom of two girls and lives in Manhattan. Read her inaugural column below, and follow her reports at CNN Parents and on Twitter .

(CNN) -- Every time a dad at my 5-year-old daughter's basketball practice screams from the sidelines urging his son to run faster and shoot better, I cringe and wonder whether he's trying to live out his own failed hoop dreams through his son. When I see this same dad take to the court after practice and try to shoot like Michael Jordan, I think my theory is right.

And now a study, for the first time, backs it up.

Published in the journal PLOS One, the study is the first to investigate what motivates those sports dads like the one I mentioned and the stage moms you have no doubt witnessed at ballet class and gymnastics.

Researchers worked with 73 parents (89% were moms) from the Netherlands who were, on average, around 43 years old and had children between the ages of 8 and 15. They found that the parents who often saw their children as part of themselves were more likely motivated by their own unfulfilled dreams and ambitions.

"I think this is something that has long been assumed, and never supported through research," said Dr. Jennifer Hartstein, a New York City-based child, adolescent and family psychologist and author of the book, "Princess Recovery: A How-to Guide to Raising Strong, Empowered Girls Who Can Create Their Own Happily Ever Afters."

"It's a small study, but it is meaningful in that it highlights how this could be detrimental to children."

While the study did not explore specifically whether these so-called stage parents can harm their kids, Hartstein, who appears regularly on network television news programs including on CNN, said they can, especially when their kids' activities serve them as much as their child.

"If a father was a failed guitar player, he may really push his child to learn the guitar, to practice all the time, and focus on being the best in that area," said Hartstein. "This is harmful because it minimizes the child's ability to make decisions for himself. The parent looks at his child as an extension of himself, rather than as his own person."

The end result could be a child feeling less confident in his or her own abilities, and worrying too much about mom or dad. "This kind of pressure can also lead a child to fear disappointing his parent, as he is aware, on some level, that his parent is living vicariously through him," she said.

That is exactly what I think about when I see my daughter's teammate on the basketball court; I wonder how much he's worrying about not shooting as well as his daddy wishes he could.

How much do you push?Now while many of us, myself included, might not be stage parents (or admit it!), we often want to encourage our kids, maybe even put pressure on them to do things they don't want to do. But how much do you push? My 7-year-old seems to be a natural in gymnastics and dance, but she doesn't want to take any more gymnastics or dance classes. Do I push her to take them even though she says no?

As I struggled with that question, I remembered an interview I did with first lady Michelle Obama when I was at iVillage.com. Obama admitted that Malia, who turns 15 in July, and has played tennis since she was little, wanted to give up the sport at one point but the first lady wouldn't let her.

"I just sort of said, look, you're going to do tennis, and you're going to do tennis because I want you to do an individual sport. It's not about you being a good tennis player. It's about you learning how to stick with something hard and get better at it ... because that's ... what life is," the first lady told me during the informal interview last summer in her East Wing office. "Life is getting through stuff that's hard, teaching yourself that you can do hard things and you get better at them and then they get easier."

Beth Engelman, co-founder of the blog Mommy on a Shoestring, said if her 7-year-old son had his way, he'd only play soccer, but she pushes him to take karate and tennis lessons, too.

"He hates it, but I make him do it ... because I want him to at least have that well-roundedness," she said. "I think that it's so easy in this day and age to be like alright, fine, more down time, but I think it's good to sort of push them at least until they get to middle school and then they can make their own decision."

Hartstein said there is a "fine line" between encouragement and pressure, and that we, as parents, need to be honest with ourselves about where we fall on that line.

"Encouraging your child to be the best, to work her hardest, to challenge herself to achieve great things is great," she said. "Pushing them to the brink, where the emotions are always at the surface, and ignoring when there is some shut-down, is not healthy and could be detrimental to your child. It could actually lead to self-esteem issues, depression, anxiety and other mental health related issues."

We've all heard the tragic tale of the successful child actor who burned out in a haze of drugs and dysfunction after hitting his teens. Or the elite young athlete who never wants to touch a racket again after a lifetime of training to the breaking point. Pushing a kid to the top can be perilous.

How to avoid becoming a stage mom or dadThe best advice, Hartstein said, is to talk with your child and take time to really listen. We, as parents, should be checking in to find out how our kids are responding to our pressure and to gauge what their resistance is really about. But the biggest advice is probably this: We need to determine the reason we are pushing in the first place. Is it for our child or solely for us?

So I keep asking myself whether my desire to see my daughter take dance and gymnastics is more about me, since I enjoyed both activities as a kid. Is it because I know she's good at both and I want to push her, as in the case of Malia Obama, to keep going until she gets really good and can then decide if she wants to give them up?

I haven't figured out those answers yet, so for now, her dance and gymnastics future is on hold, but I admit I have those class schedules at the ready -- just in case!