- Back to Home »

- New mystery at Richard III burial site

- Archaeologists found a lead coffin within a stone coffin near Richard III's grave

- The identity of its occupant is unknown, but there are three prestigious contenders

- The confirmation this year of the discovery of Richard's remains drew global interest

- The excavation site is at a parking lot in the central English city of Leicester

(CNN) -- First came the dramatic discovery of the long-lost remains of King Richard III.

Now, there's the mystery of the coffin within the coffin.

Archaeologists working at the site in central England where Richard III's body was found underneath a parking lot are currently puzzling over a sealed lead coffin containing the remains of a yet-to-be-identified person.

The lead coffin was found encased in a larger stone coffin.

The smaller coffin is intact "except for a hole at one end of the casket through which we could tantalizingly see someone's feet," said Mathew Morris, the fieldwork director at the site.

New discovery just as exciting

Last year, archaeologists unearthed a body buried beneath a nondescript parking lot in the city of Leicester. In February, they confirmed the body was that of Richard III, the last king of England to die on the battlefield.

British scientists announced Monday, February 4, that they are convinced "beyond reasonable doubt" that a skeleton found during an archaeological dig in Leicester, central England, in August 2012 is that of the former king, who was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485.

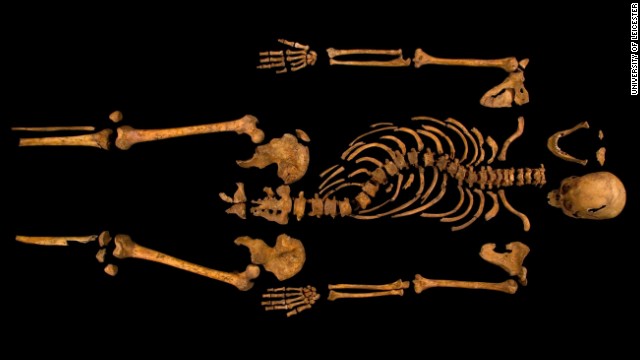

British scientists announced Monday, February 4, that they are convinced "beyond reasonable doubt" that a skeleton found during an archaeological dig in Leicester, central England, in August 2012 is that of the former king, who was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485.  Mitochondrial DNA extracted from the bones was matched to Michael Ibsen, a Canadian cabinetmaker and direct descendant of Richard III's sister, Anne of York. As the skeleton was being excavated, a notable curve in the spine could be seen. The body was found in a roughly-hewn grave, which experts say was too small for the body, forcing it to be squeezed in to an unusual position. The positioning also shows that his hands may have been tied.

Mitochondrial DNA extracted from the bones was matched to Michael Ibsen, a Canadian cabinetmaker and direct descendant of Richard III's sister, Anne of York. As the skeleton was being excavated, a notable curve in the spine could be seen. The body was found in a roughly-hewn grave, which experts say was too small for the body, forcing it to be squeezed in to an unusual position. The positioning also shows that his hands may have been tied.  Archaeologists say their examination of the skeleton shows Richard met a violent death: They found evidence of 10 wounds -- eight to the head and two to the body -- which they believe were inflicted at or around the time of death. Here, a cut mark on the right rib can be seen.

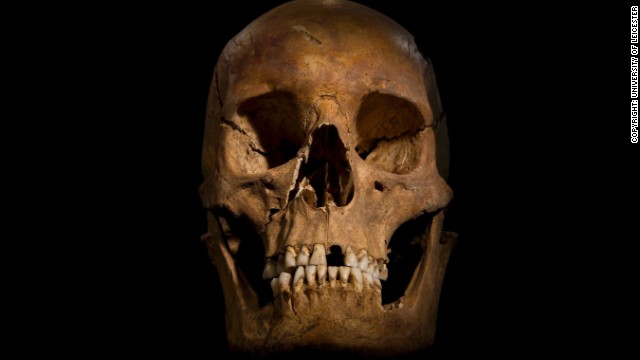

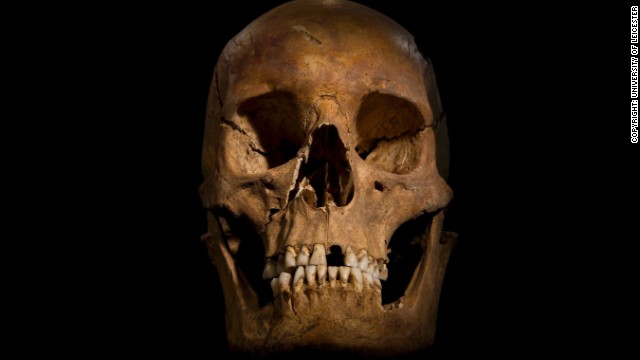

Archaeologists say their examination of the skeleton shows Richard met a violent death: They found evidence of 10 wounds -- eight to the head and two to the body -- which they believe were inflicted at or around the time of death. Here, a cut mark on the right rib can be seen.  The lower jaw shows a cut mark caused by a knife or dagger. The archaeologists say the wounds to Richard's head could have been what killed him and suggest he may have lost his helmet during his last battle.

The lower jaw shows a cut mark caused by a knife or dagger. The archaeologists say the wounds to Richard's head could have been what killed him and suggest he may have lost his helmet during his last battle.  Here, a wound to the cheek, possibly caused by a square-bladed dagger, can be seen.

Here, a wound to the cheek, possibly caused by a square-bladed dagger, can be seen.  This hole in the top of the skull represents a penetrating injury to the top of the head.

This hole in the top of the skull represents a penetrating injury to the top of the head.  Two flaps of bone, related to the penetrating injury to the top of the head, can clearly be seen on the interior of the skull.

Two flaps of bone, related to the penetrating injury to the top of the head, can clearly be seen on the interior of the skull.  The image shows a blade wound to the pelvis, which has penetrated all the way through the bone.

The image shows a blade wound to the pelvis, which has penetrated all the way through the bone.  Here, the complete spine is displayed. The width of the curve is correct, but the gaps between vertebrae have been increased to prevent damage from them touching one another.

Here, the complete spine is displayed. The width of the curve is correct, but the gaps between vertebrae have been increased to prevent damage from them touching one another.  Here, the complete skeleton is laid out, showing the spine's dramatic curve.

Here, the complete skeleton is laid out, showing the spine's dramatic curve.  The remains of King Richard III

The remains of King Richard III  The king in the parking lot

The king in the parking lot  Tracking down Richard III's remains

Tracking down Richard III's remains  The woman who found Richard III

The woman who found Richard III The news drew global attention and set off a debate over Richard's bloodthirsty reputation.

Archaeologists from the University of Leicester, who have been toiling away at the site this summer, say the discovery of the double coffin is just as exciting.

They only uncovered the lead coffin last week after eight people hauled the heavy lid off the stone coffin. But figuring out who's inside looks set to be a much tougher task.

"This inner coffin is likely to contain a high-status burial, although we still don't know who it contains," Morris wrote in a blog post. "No writing was visible on the coffin lid but it does bear a crude cross soldered into the metal."

There are three main contenders for the identity of the coffin's inhabitant: a medieval knight named Sir William de Moton of Peckleton, and two leaders of the English Grey Friars order, Peter Swynsfeld and William of Nottingham.

Beneath the parking lot

The Leicester site is where a church, known as Grey Friars Friary, once stood.

Over the centuries, the whereabouts of the friary's remnants were forgotten, but it remained in the records as the burial place of Richard III.

Last year, experts began digging away at the area, which had taken on the less illustrious role of a parking lot. They went on to establish that it was part of the friary and that a skeleton, hastily buried in an uneven grave, was that of Richard.

The archaeologists who undertook a new dig this summer think the double coffin, located near Richard's grave, was buried during the 14th century, more than 100 years before Richard was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485.

Of the coffin's three likely occupants, Swynsfeld died in 1272, William of Nottingham died in 1330 and Sir William de Moton died between 1356 and 1362.

'A first for all of us'

Besides the puzzle of who lies within, the archaeologists were excited about the coffins themselves.

"This was a first for all of us on site," Morris said. "None of the team had ever excavated an intact stone coffin before, let alone a lead coffin as well."

They have now wrapped up their four weeks of digging at the site. The lead coffin has been taken away so that experts can carry out tests to figure out the best way of opening it without damaging its contents.

But, Morris said, other parts of the friary that the archaeologists tried to investigate this summer appear to have been completely destroyed -- meaning that some of the site's mysteries may never be solved.