- Back to Home »

- JFK grandson: Civil rights, 50 years later

The Voting Rights Act is often called the crown jewel of the civil rights movement, yet many Americans do not know why or how it was passed. Pictured, NAACP Field Director Charles White speaks on the steps of the U.S. Supreme Court on Tuesday, June 25, after the court limited use of a major part of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, in effect invalidating a key enforcement provision. Here are some key moments and characters in the voting rights saga.

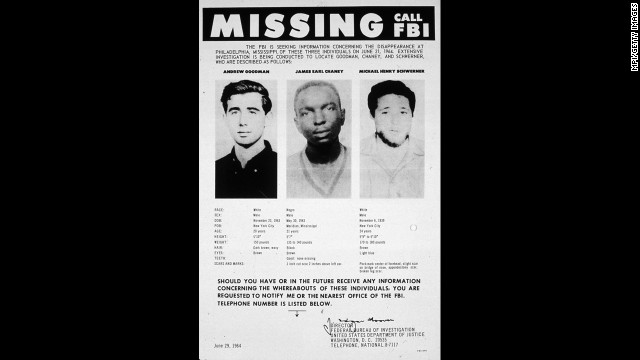

The Voting Rights Act is often called the crown jewel of the civil rights movement, yet many Americans do not know why or how it was passed. Pictured, NAACP Field Director Charles White speaks on the steps of the U.S. Supreme Court on Tuesday, June 25, after the court limited use of a major part of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, in effect invalidating a key enforcement provision. Here are some key moments and characters in the voting rights saga.  Three young civil rights workers were murdered in 1964 in Mississippi while trying to register black voters. The infamous murders showed that segregationists were willing to kill to keep African-Americans from voting.

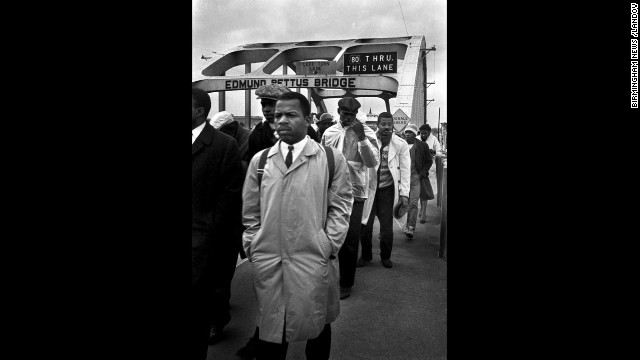

Three young civil rights workers were murdered in 1964 in Mississippi while trying to register black voters. The infamous murders showed that segregationists were willing to kill to keep African-Americans from voting.  John Lewis, a young activist who later became a congressman of Georgia, heads to a fateful encounter on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama during a 1965 march. Lewis was brutally assaulted by state troopers during the "Bloody Sunday" march that made voting rights a national issue.

John Lewis, a young activist who later became a congressman of Georgia, heads to a fateful encounter on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama during a 1965 march. Lewis was brutally assaulted by state troopers during the "Bloody Sunday" march that made voting rights a national issue.  Marchers during the 1965 voting rights campaign in Selma, Alabama gather for a rally on March 26, 1965, a few weeks after "Bloody Sunday." Black residents were beaten, fired from their jobs and imprisoned trying to vote.

Marchers during the 1965 voting rights campaign in Selma, Alabama gather for a rally on March 26, 1965, a few weeks after "Bloody Sunday." Black residents were beaten, fired from their jobs and imprisoned trying to vote.  Viola Liuzzo, a Detroit housewife, was murdered while participating in the voting rights campaign in Selma, Alabama, in 1965. Her death outraged the nation and helped spur passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Viola Liuzzo, a Detroit housewife, was murdered while participating in the voting rights campaign in Selma, Alabama, in 1965. Her death outraged the nation and helped spur passage of the Voting Rights Act.  President Lyndon Johnson, pictured here discussing the act with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1965, went on national television to call for passage of the Voting Rights Act. He ended his speech by saying, "And we shall overcome."

President Lyndon Johnson, pictured here discussing the act with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1965, went on national television to call for passage of the Voting Rights Act. He ended his speech by saying, "And we shall overcome."  Rep. John Lewis speaks after bipartisan House and Senate officials met to voice support for reauthorizing the Voting Rights Act for an additional 25 years on May 2, 2006. From left, Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid, House Speaker Dennis Hastert, Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist and other officials listen during the media conference.

Rep. John Lewis speaks after bipartisan House and Senate officials met to voice support for reauthorizing the Voting Rights Act for an additional 25 years on May 2, 2006. From left, Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid, House Speaker Dennis Hastert, Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist and other officials listen during the media conference.  President George W. Bush signs reauthorization of the act on July 27, 2006. From left, Rep. John Conyers, D-Michigan, Rep. James Sensenbrenner, R-Wisconsin, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, D-California, Sen. Harry Reid, D-Nevada, and Sen. Bill Frist, R-Tennessee, look on.

President George W. Bush signs reauthorization of the act on July 27, 2006. From left, Rep. John Conyers, D-Michigan, Rep. James Sensenbrenner, R-Wisconsin, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, D-California, Sen. Harry Reid, D-Nevada, and Sen. Bill Frist, R-Tennessee, look on.  President Barack Obama marches with civil right veterans during a commemoration march in 2007.

President Barack Obama marches with civil right veterans during a commemoration march in 2007.  A conservative judge called the Voting Rights Act a racial entitlement but supporters of the act say it is the crowning victory of the civil rights movement. Pictured, people gather for a post-march rally after crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge on the "Bloody Sunday" anniversary, March 4, 2012.

A conservative judge called the Voting Rights Act a racial entitlement but supporters of the act say it is the crowning victory of the civil rights movement. Pictured, people gather for a post-march rally after crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge on the "Bloody Sunday" anniversary, March 4, 2012.  Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law Executive Director Barbara Arnwine speaks during a news conference to voice opposition to state photo ID voter laws with the Rev. Jesse Jackson and members of Congress at the U.S. Capitol July 13, 2011.

Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law Executive Director Barbara Arnwine speaks during a news conference to voice opposition to state photo ID voter laws with the Rev. Jesse Jackson and members of Congress at the U.S. Capitol July 13, 2011.  A supporter of the Voting Rights Act rallies in the South Carolina State House in Columbia on February 26, 2013, the day before oral hearings at the Supreme Court.

A supporter of the Voting Rights Act rallies in the South Carolina State House in Columbia on February 26, 2013, the day before oral hearings at the Supreme Court.  The Rev. Jesse Jackson, at the microphone, and the Rev. Al Sharpton, left, deliver remarks during a rally outside the U.S. Supreme Court on February 27, 2013, as the court prepared to hear oral arguments in Shelby County v. Holder, the legal challenge to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, at the microphone, and the Rev. Al Sharpton, left, deliver remarks during a rally outside the U.S. Supreme Court on February 27, 2013, as the court prepared to hear oral arguments in Shelby County v. Holder, the legal challenge to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act.  Supporters of the Voting Rights Act listen to speakers discussing the rulings outside the U.S. Supreme Court building on Tuesday, June 25.

Supporters of the Voting Rights Act listen to speakers discussing the rulings outside the U.S. Supreme Court building on Tuesday, June 25.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

- This month marks 50th anniversary of the March on Washington

- JFK grandson Jack Schlossberg says Supreme Court wrong on Voting Rights Act

- He says the ruling in June struck down vital protection for the right to vote

- Schlossberg: Use 50th anniversary to recommit to protect voting rights

Editor's note: Jack Schlossberg is a junior at Yale University, a contributor to the Yale Daily News and The Yale Herald. He is the grandson of President John F. Kennedy.

(CNN) -- On Wednesday, August 28, 1963, hundreds of thousands of Americans marched on the National Mall in support of civil rights. From the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his iconic "I Have a Dream" speech, asserting the paramount importance of civil rights for all.

The march forced the issue of civil rights onto the national agenda and into the lives of every American of every race. It was the culmination of years of tireless work and perseverance, all involving tremendous risk and quiet courage, much of it receiving little or no attention.

Wednesday, August 28, is the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington. The march was one of the proudest days in our nation's history, a day when all Americans heard what it might sound like to "hear freedom ring." People gathered in excitement over the potential of major progress in the centuries-long struggle for American equality.

In June 1963, President John F. Kennedy had become the first American president to deem civil rights a "moral issue," stating that it was an issue "as old as the Scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution," that America "will not be fully free until all its citizens are free." Kennedy, however, was assassinated before seeing the full legislative fruits of his labor.

Following this inspiring March on Washington and with the strong support of President Lyndon Johnson, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, both major pieces of legislation that placed the primary responsibility and power to protect every citizen's right to vote with the federal government.

Never again would the United States revert to the injustice and immorality of Jim Crow laws, poll taxes and literacy tests that defined and preserved systemic racial inequality in the South before the March on Washington.

Today, the most vital provision of the Voting Rights Act, in effect, no longer exists. The preclearance provision of Section 5 requires Justice Department approval of any significant voting change in a set of nine states and parts of six others covered by a formula in Section 4 on the basis of the states' history of racial discrimination in voting.

Rep. John Lewis: Ruling is a 'dagger'

Rep. John Lewis: Ruling is a 'dagger'  High court halts key civil rights law

High court halts key civil rights law Although Attorney General Eric Holder is wisely taking Texas to court under Section 3, experts insist that the crucial remedy was the preventive one provided by Sections 4 and 5. Yet in June, the Supreme Court struck down Section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder.

The court argued that the problem of voter disenfranchisement on the basis of race can no longer be assumed to persist in the jurisdictions identified after extensive congressional hearings in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 2000s. Therefore, the court decided, the crucial means of oversight -- pre-clearance review -- granted to the federal government in Sections 4(b) and 5 might no longer be necessary to secure the ends -- the right of every eligible citizen to vote -- for which those provisions were enacted and frequently re-enacted. Instead, the list of covered jurisdictions would need to be updated by Congress in a continuing manner on the basis of ever-changing data.

Many legal scholars across the ideological spectrum have explained why this unprecedented decision violates long-settled constitutional principles under both the Enforcement Clause of the 14th Amendment and the long-established principle and practice, established in McCulloch v. Maryland. The "McCulloch test" requires the court to defer to Congress regarding which means are necessary to achieve legitimate ends, so long as those means do not cross established constitutional boundaries among the branches of government or between government and individuals.

I am not a legal scholar, but I argue that there is another, more basic and compelling reason rooted in legal precedent why the court was mistaken.

Precedent dictates that the Supreme Court should exercise extreme restraint in extraordinary situations known as "political questions." In Baker v. Carr, the court outlined the factors that identified the existence of purely "political questions." One of those factors is "the impossibility of a court's undertaking independent resolution without expressing lack of the respect due coordinate branches of government."

I do not claim that the constitutionality of the Voting Rights Act is literally a "political question" entirely beyond the purview of the federal courts; such questions, I understand, are truly few and far between. What I do argue, however, is that many of the same factors that instruct the court to exercise restraint regarding political questions are applicable here. Namely, the court had every reason to defer to congressional expertise and political accountability when hearing this case.

In Shelby County v. Holder, the court entered into the political arena, heedless of the need for caution and deference, and the resulting decision expressed a blatant lack of respect for the other branches of government and, by extension, for the American people.

The Voting Rights Act is a monument to the long struggle, over more than a century, for racial equality. The act became law because of the courage and devotion of those involved in the civil rights movement and our country, and our government has, since the act's original passage, understood its significance as something more meaningful than just one more act of Congress.

In fact, the act is extraordinary in that it has been consistently revisited and reaffirmed by both Democrats and Republicans since its passage almost 50 years ago.

Included in the 1965 law was a clause stating that unless Congress voted to extend the Voting Rights Act, it would expire after five years. In 1970, under President Nixon, Congress renewed the act for five more years. In 1975, under President Ford, Congress again renewed it for another seven years. In 1982, under President Reagan, Congress reauthorized it for 25 years, and in 2006, under President Bush, Congress did so again for another 25 years. Each of these presidents signed renewals of the act.

I will probably never be denied the right to vote. I am a white male with a valid form of identification living in a progressive state. In November, when I cast my first vote in a national election, I felt excited, proud and part of something larger than myself. I have trouble believing that I will be as excited and proud to participate in an election in which my peers won't have the same protection against voter discrimination as they did last fall.

My whole life, I have heard that if one person in every precinct had voted differently or if one less supporter had made it to the polls, my grandfather would not have been elected president in 1960. Voting matters.

In Shelby County v. Holder, the Supreme Court showed a lack of respect for the efforts of all those who, both in government and out, worked over the generations to uphold America's ongoing efforts to fulfill its promise of equality under the law. The ruling effectively erased a landmark piece of legislation that secured the culmination of a century-long struggle toward justice and equality for African-Americans and minorities in America.

Beyond its implications in the present, Voting Rights Act itself is a monument to all those who fought for a voice and a vote.

Not since Reconstruction had our government acted so strongly in the name of civil rights. In his majority opinion in Shelby County v. Holder, Chief Justice John Roberts explained how successful the act has been in limiting racial disenfranchisement, which "is no longer the problem it once was." He conceded that "these improvements are in large part because of the Voting Rights Act" itself. That argument makes logical sense only if one believes that discrimination in voting in America no longer exists. But, I think most of us would agree that is not that case.

The law was successful because it created an effective protection against racism by allowing the federal government to stop disenfranchisement before it became law, not after it became part of a local electoral system. As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote in her dissenting opinion, eliminating this law is "like throwing away your umbrella in a rain storm."

Jack Schlossberg

The act's effectiveness makes it an important symbol of the good that government can do. It reminds Americans that their government is capable of effective action and is committed to fostering a genuine democracy for everyone.

The civil rights movement didn't end on August 6, 1965. It continued because the work of creating a truly equal country never ends. Racism plagued America throughout the '60s, into the '70s, through the '80s; it continued in the '90s and in the first decade of the new millennium; and it persists today.

King's dream was not that he would be able to stop marching in a few years, once things got a little bit better. Racism and inequality may not be as severe as before, but when "stand your ground" laws in Florida protect those many believe to be guilty of racially motivated violence, then surely there is work to be done. And when state legislatures put new barriers in the way of voters, turning them away for not having certain forms of ID, then clearly we have yet to perfect the very process that makes America the democracy it promises to be for all of its citizens.

On Wednesday, August 28, let's remember all the work that still needs to be done.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter.

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Jack Schlossberg.