- Back to Home »

- 3 ways to fix the Supreme Court

The justices of the U.S. Supreme Court sit for their official photograph on October 8, 2010, at the Supreme Court. Front row, from left: Clarence Thomas, Antonin Scalia, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Anthony M. Kennedy and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Back row, from left: Sonia Sotomayor, Stephen Breyer, Samuel Alito Jr. and Elena Kagan.

The justices of the U.S. Supreme Court sit for their official photograph on October 8, 2010, at the Supreme Court. Front row, from left: Clarence Thomas, Antonin Scalia, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Anthony M. Kennedy and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Back row, from left: Sonia Sotomayor, Stephen Breyer, Samuel Alito Jr. and Elena Kagan.  In 2005, Chief Justice John G. Roberts was nominated by President George W. Bush to succeed Justice Sandra Day O'Connor as an associate justice. After Chief Justice William Rehnquist died, however, Bush named Roberts to the chief justice post. The court has moved to the right during his tenure, although Roberts supplied the key vote to uphold President Barack Obama's Affordable Care Act.

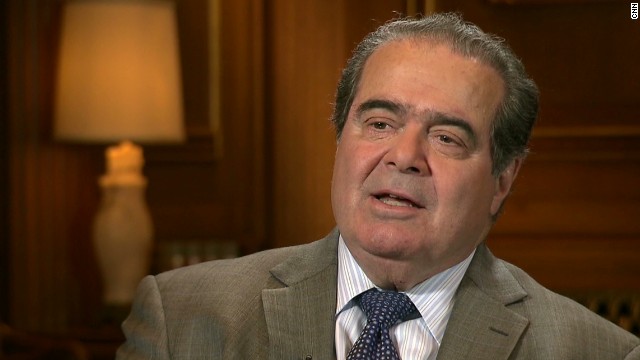

In 2005, Chief Justice John G. Roberts was nominated by President George W. Bush to succeed Justice Sandra Day O'Connor as an associate justice. After Chief Justice William Rehnquist died, however, Bush named Roberts to the chief justice post. The court has moved to the right during his tenure, although Roberts supplied the key vote to uphold President Barack Obama's Affordable Care Act.  Justice Antonin Scalia was appointed by President Ronald Reagan in 1986 to fill the seat vacated by Justice William Rehnquist when he was elevated to chief justice. A constitutional originalist -- and a colorful orator -- Scalia is a member of the court's conservative wing. He is currently the court's longest-serving justice.

Justice Antonin Scalia was appointed by President Ronald Reagan in 1986 to fill the seat vacated by Justice William Rehnquist when he was elevated to chief justice. A constitutional originalist -- and a colorful orator -- Scalia is a member of the court's conservative wing. He is currently the court's longest-serving justice.  Justice Anthony M. Kennedy was appointed to the court by President Ronald Reagan in 1988. He is a conservative justice but has provided crucial swing votes in many cases, writing the majority opinion, for example, in Lawrence v. Texas, which struck down that state's sodomy law.

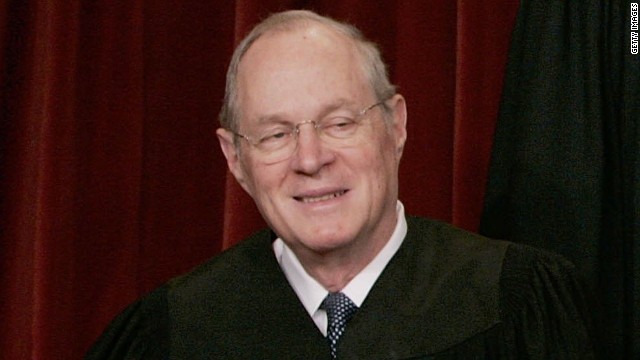

Justice Anthony M. Kennedy was appointed to the court by President Ronald Reagan in 1988. He is a conservative justice but has provided crucial swing votes in many cases, writing the majority opinion, for example, in Lawrence v. Texas, which struck down that state's sodomy law.  Justice Clarence Thomas is the second African-American to serve on the court, succeeding Justice Thurgood Marshall when he was appointed by President George H. W. Bush in 1991. He is a conservative, a strict constructionist who supports states' rights.

Justice Clarence Thomas is the second African-American to serve on the court, succeeding Justice Thurgood Marshall when he was appointed by President George H. W. Bush in 1991. He is a conservative, a strict constructionist who supports states' rights.  Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is the second woman to serve on the Supreme Court. Appointed by President Bill Clinton in 1993, she is a strong voice in the court's liberal minority.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is the second woman to serve on the Supreme Court. Appointed by President Bill Clinton in 1993, she is a strong voice in the court's liberal minority.  Justice Stephen G. Breyer was appointed to the court in 1994 by President Bill Clinton. He is considered a member of the court's liberal minority.

Justice Stephen G. Breyer was appointed to the court in 1994 by President Bill Clinton. He is considered a member of the court's liberal minority.  Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. was appointed by President George W. Bush in 2006 and is known as one of the most conservative justices to serve on the court in modern times.

Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. was appointed by President George W. Bush in 2006 and is known as one of the most conservative justices to serve on the court in modern times.  Justice Sonia Sotomayor is the court's first Hispanic and third female justice. She was appointed by President Barack Obama in 2009 and is regarded as a resolutely liberal member of the court.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor is the court's first Hispanic and third female justice. She was appointed by President Barack Obama in 2009 and is regarded as a resolutely liberal member of the court.  Justice Elena Kagan is the fourth female justice and a member of the court's liberal wing. She was appointed in 2010, at the age of 50, by President Barack Obama and is the court's youngest member.

Justice Elena Kagan is the fourth female justice and a member of the court's liberal wing. She was appointed in 2010, at the age of 50, by President Barack Obama and is the court's youngest member. - Eric Segall: Life tenure allows justices to serve past the point of competence

- Segall: Court should follow lead of many states and allow cameras in courtroom

- The Supreme Court nomination process is a farce, he adds

Editor's note: Eric Segall is the Kathryn and Lawrence Ashe Professor of Law at Georgia State University College of Law. He has written more than 25 law review articles on the Supreme Court and the Constitution as well as numerous op-eds and essays. He is the author of "Supreme Myths: Why the Supreme Court is not a Court and its Justices are not Judges." He tweets regularly at @espinsegall.

(CNN) -- Less than three months ago, the Supreme Court of the United States handed down eagerly awaited rulings on same-sex marriage, voting rights and affirmative action. Next month, the court will begin its new term and likely deal with controversial issues such as abortion, campaign finance reform and the separation of church and state.

When the court is in the middle of a term, it is easy to focus on hard legal questions, the legal views of individual justices and the consequences of landmark decisions. Now is a good time, when the court is in recess, to take a step back and look at the institution itself.

A lifetime is too long

First, our Supreme Court justices are the only judges in the world who sit on a country's highest court and have life tenure. Because the president nominates the justices and the Senate confirms them, the American people do not elect the justices and cannot vote them out of office. In light of the crucial role the court plays across the spectrum of social, legal and political issues, the question of how long our justices serve should be re-examined.

Supreme Court justices often serve more than 25 years and beyond the time they are still fit to perform their duties. For example, according to renown author David Garrow, both Justices William O. Douglas and Thurgood Marshall remained on the bench well after their skills had significantly diminished beyond the point of competence.

The usual justification for life tenure is that the justices need to be independent of the other branches of the government to adequately perform their duties. This need for independence is real and compelling, but there are other ways to achieve that goal.

Other countries use fixed terms, retirement ages or a combination of the two to achieve the necessary independence. There simply is no persuasive reason to allow governmental officials who have virtually unreviewable power to hold their offices for life.

Few witnesses to history

The second aspect of our Supreme Court that needs to be changed is the lack of television coverage of oral arguments and decision announcements. What a shame that during the last week of June when the court handed down and read from the bench numerous important decisions -- including the overturning of the Defense of Marriage Act and the formula in Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act -- the American people had to hear the news indirectly from media personalities instead of the justices.

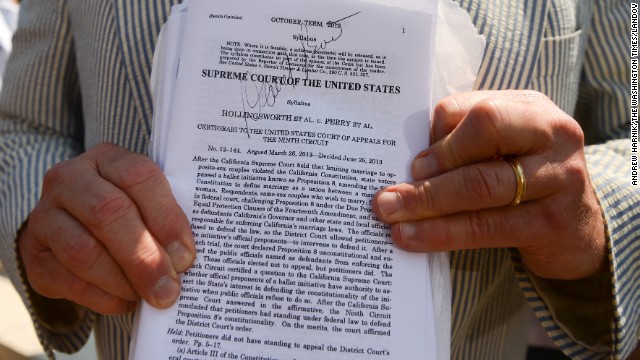

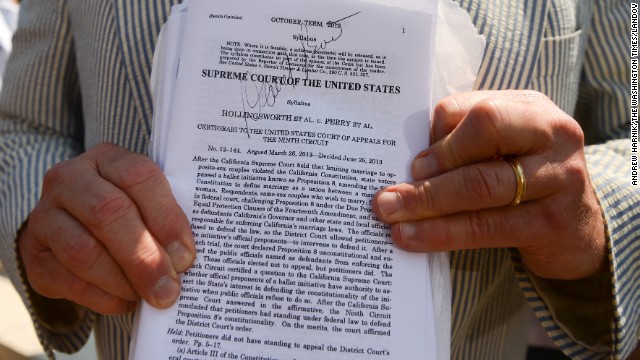

Hollingsworth v. Perry (2013): The Supreme Court dismissed an appeal over California's Proposition 8 on jurisdictional grounds. The voter-approved ballot measure barring same-sex marriage was not defended by state officials, but rather a private party. This ruling cleared the way for same-sex marriage in California to resume, but left open-ended the legal language of 35 other states barring same-sex marriage. Take a look at other important cases decided by the high court.

Hollingsworth v. Perry (2013): The Supreme Court dismissed an appeal over California's Proposition 8 on jurisdictional grounds. The voter-approved ballot measure barring same-sex marriage was not defended by state officials, but rather a private party. This ruling cleared the way for same-sex marriage in California to resume, but left open-ended the legal language of 35 other states barring same-sex marriage. Take a look at other important cases decided by the high court.  United States v. Windsor (2013): When her wife died in 2009, Edith Windsor, 84, was forced to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in estate taxes because her marriage was not recognized by the federal government's Defense of Marriage Act of 1996. The Supreme Court struck down the part of the law which denied legally marriage same-sex couples the same federal benefits provided to heterosexual spouses.

United States v. Windsor (2013): When her wife died in 2009, Edith Windsor, 84, was forced to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in estate taxes because her marriage was not recognized by the federal government's Defense of Marriage Act of 1996. The Supreme Court struck down the part of the law which denied legally marriage same-sex couples the same federal benefits provided to heterosexual spouses.  National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012): The Supreme Court upheld most of the Affordable Care Act, the Obama administration's health care reform law, on June 28, 2012. The decision determined how hundreds of millions of Americans will receive health care.

National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012): The Supreme Court upheld most of the Affordable Care Act, the Obama administration's health care reform law, on June 28, 2012. The decision determined how hundreds of millions of Americans will receive health care.  Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010): Activists rally in February 2012 to urge the Supreme Court to overturn its decision that fundamentally changed campaign finance law by allowing corporations and unions to contribute unlimited funds to political action committees not affiliated with a candidate.

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010): Activists rally in February 2012 to urge the Supreme Court to overturn its decision that fundamentally changed campaign finance law by allowing corporations and unions to contribute unlimited funds to political action committees not affiliated with a candidate.  Texas v. Johnson (1989): The Supreme Court overturned the decision that convicted Gregory Lee Johnson of desecrating a venerated object after he set an American flag on fire during a protest. The court ruled that Johnson (at right with his lawyer, William Kunstler) was protected under the First Amendment right to freedom of speech.

Texas v. Johnson (1989): The Supreme Court overturned the decision that convicted Gregory Lee Johnson of desecrating a venerated object after he set an American flag on fire during a protest. The court ruled that Johnson (at right with his lawyer, William Kunstler) was protected under the First Amendment right to freedom of speech.

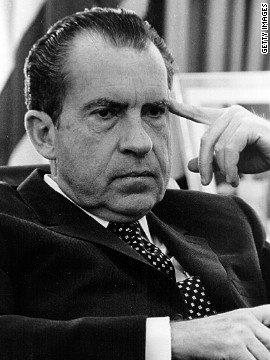

United States v. Nixon (1974): When President Richard Nixon claimed executive privilege over taped conversations regarding the Watergate scandal, the Supreme Court ruled that he had to turn over the tapes and other documents. The ruling set a precedent limiting the power of the president of the United States.

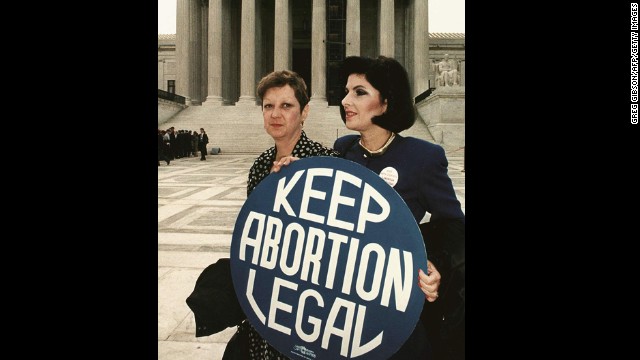

Roe v. Wade (1973): Norma McCorvey, identified as "Jane Roe," sued Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade over a law that made it a felony to have an abortion unless the life of the mother was in danger. The court agreed with Roe and overruled any laws that made abortion illegal in the first trimester. Here, McCorvey, left, stands with her attorney Gloria Allred in 1989.

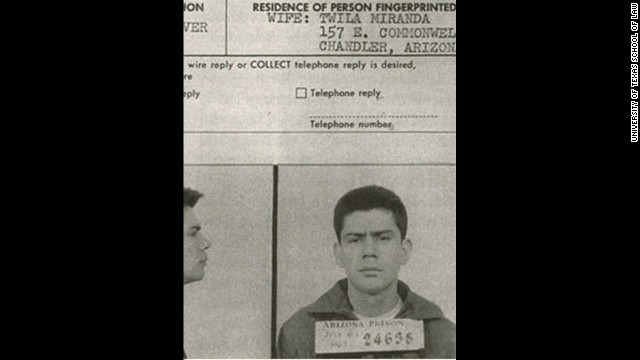

Roe v. Wade (1973): Norma McCorvey, identified as "Jane Roe," sued Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade over a law that made it a felony to have an abortion unless the life of the mother was in danger. The court agreed with Roe and overruled any laws that made abortion illegal in the first trimester. Here, McCorvey, left, stands with her attorney Gloria Allred in 1989.  Miranda v. Arizona (1966): Ernesto Miranda confessed to a crime without the police informing him of his right to an attorney or right against self-incrimination. His attorney argued in court that the confession should have been inadmissible, and in 1966, the Supreme Court agreed. The term "Miranda rights" has been used since.

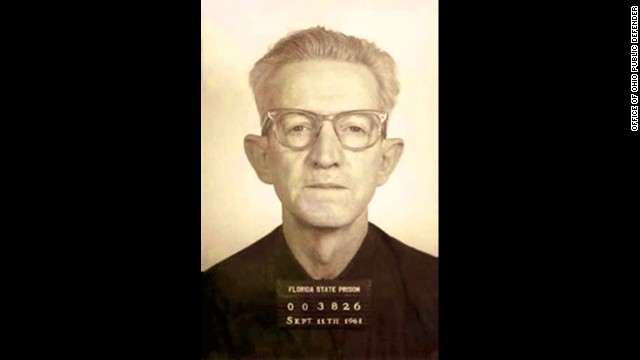

Miranda v. Arizona (1966): Ernesto Miranda confessed to a crime without the police informing him of his right to an attorney or right against self-incrimination. His attorney argued in court that the confession should have been inadmissible, and in 1966, the Supreme Court agreed. The term "Miranda rights" has been used since.  Gideon v. Wainwright (1963): The Supreme Court overturned the burglary conviction of Clarence Earl Gideon after he wrote to the court from his prison cell, explaining he was denied the right to an attorney at his 1961 trial.

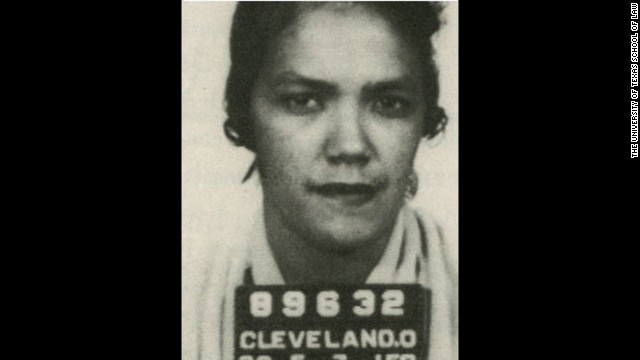

Gideon v. Wainwright (1963): The Supreme Court overturned the burglary conviction of Clarence Earl Gideon after he wrote to the court from his prison cell, explaining he was denied the right to an attorney at his 1961 trial.  Mapp v. Ohio (1961): The Supreme Court overturned the conviction of Dollree Mapp because the evidence collected against her was obtained during an illegal search. The ruling re-evaluated the Fourth Amendment, which protects citizens against unreasonable searches and seizures.

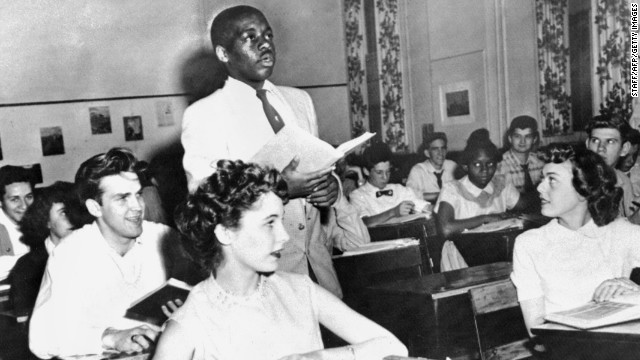

Mapp v. Ohio (1961): The Supreme Court overturned the conviction of Dollree Mapp because the evidence collected against her was obtained during an illegal search. The ruling re-evaluated the Fourth Amendment, which protects citizens against unreasonable searches and seizures.  Brown v. Board of Education (1954): Nathaniel Steward recites his lesson surrounded by white classmates at the Saint-Dominique School in Washington. In Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional to separate students based on race.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954): Nathaniel Steward recites his lesson surrounded by white classmates at the Saint-Dominique School in Washington. In Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional to separate students based on race.  Korematsu v. United States (1944): Fred Korematsu, a Japanese-American man, was arrested after authorities found out that he claimed to be a Mexican-American to avoid an internment camp during World War II. The court ruled that the rights of an individual were not as important as the need to protect the country during wartime. In 1998, President Bill Clinton awarded Korematsu the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Korematsu v. United States (1944): Fred Korematsu, a Japanese-American man, was arrested after authorities found out that he claimed to be a Mexican-American to avoid an internment camp during World War II. The court ruled that the rights of an individual were not as important as the need to protect the country during wartime. In 1998, President Bill Clinton awarded Korematsu the Presidential Medal of Freedom.  Plessy v. Ferguson (1896): Homer Plessy was arrested when he refused to leave a whites-only segregated train car, claiming he was 7/8 white and only 1/8 black. The Supreme Court ruled that "separate but equal" facilities for blacks were constitutional, which remained the rule until Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

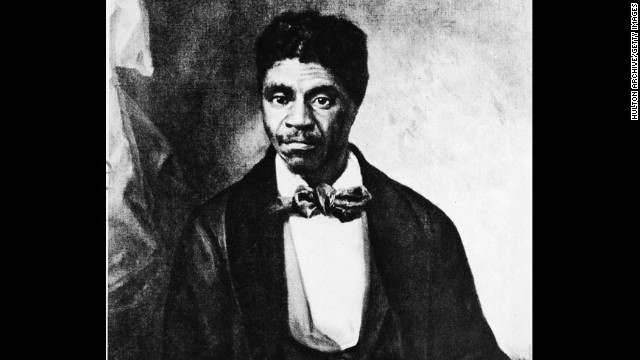

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896): Homer Plessy was arrested when he refused to leave a whites-only segregated train car, claiming he was 7/8 white and only 1/8 black. The Supreme Court ruled that "separate but equal" facilities for blacks were constitutional, which remained the rule until Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.  Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857): When Dred Scott asked a circuit court to reward him his freedom after moving to a free state, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress didn't have the right to prohibit slavery and, further, that those of African-American descent were not protected by the Constitution.

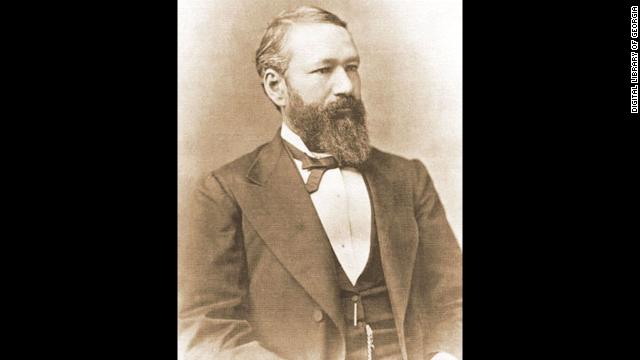

Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857): When Dred Scott asked a circuit court to reward him his freedom after moving to a free state, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress didn't have the right to prohibit slavery and, further, that those of African-American descent were not protected by the Constitution.  Gibbons v. Ogden (1824): This was the first case to establish Congress' power to regulate interstate commerce. The ruling signaled a shift in power from the states to the federal government. Aaron Ogden, seen here, was given exclusive permission from the state of New York to navigate the waters between New York and certain New Jersey ports. When Ogden brought a lawsuit against Thomas Gibbons for operating steamships in his waters, the Supreme Court sided with Gibbons.

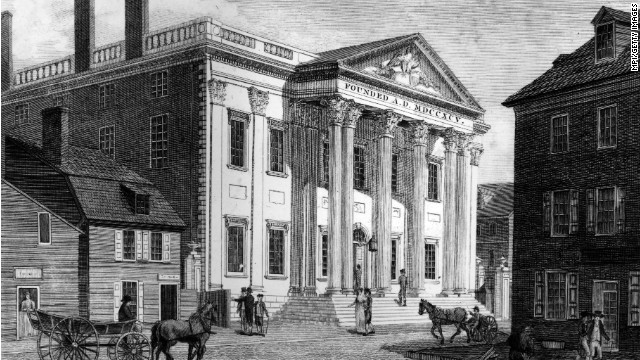

Gibbons v. Ogden (1824): This was the first case to establish Congress' power to regulate interstate commerce. The ruling signaled a shift in power from the states to the federal government. Aaron Ogden, seen here, was given exclusive permission from the state of New York to navigate the waters between New York and certain New Jersey ports. When Ogden brought a lawsuit against Thomas Gibbons for operating steamships in his waters, the Supreme Court sided with Gibbons.  McCulloch v. Maryland (1819): In response to the federal government's controversial decision to institute a national bank in the state, Maryland tried to tax the bank out of business. When a federal bank cashier, James W. McCulloch, refused to pay the taxes, the state of Maryland filed charges against him. In McCulloch v. Maryland, the Supreme Court ruled that chartering a bank was an implied power of the Constitution. The first national bank, pictured, was created by Congress in 1791 in Philadelphia.

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819): In response to the federal government's controversial decision to institute a national bank in the state, Maryland tried to tax the bank out of business. When a federal bank cashier, James W. McCulloch, refused to pay the taxes, the state of Maryland filed charges against him. In McCulloch v. Maryland, the Supreme Court ruled that chartering a bank was an implied power of the Constitution. The first national bank, pictured, was created by Congress in 1791 in Philadelphia.

Marbury v. Madison (1803): When Secretary of State James Madison, seen here, tried to stop Federal loyalists from being appointed to judicial positions, he was sued by William Marbury. Marbury was one of former President John Adams' appointees, and the court decided that although he had a right to the position, the court couldn't enforce his appointment. The case defined the boundaries of the executive and judicial branches of government.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

Photos: Supreme Court cases that changed America

Photos: Supreme Court cases that changed America Similarly in 2012, when the court held three days of oral arguments on the president's most important piece of legislation, the Affordable Care Act, the public should have been able to witness those arguments just like the lucky few who happened to be in the courtroom.

Moreover, it is close to a tragedy that future generations will have absolutely no video record of the court's arguments or decisions in these landmark cases. It would be an invaluable learning tool if young Americans today could see the oral arguments in Brown v. Board of Education or Roe v. Wade.

More than 30 state supreme courts allow cameras in the courtroom with great success. Supreme Court Justices John Roberts and Anthony Kennedy have suggested that the presence of television would lead to grandstanding by lawyers and maybe even the justices themselves, but the experiences in state courts demonstrate such concerns are greatly exaggerated.

When Arkansas was considering placing cameras in the courtroom, Justice Robert L. Brown conducted a survey and found that "state supreme courts have blazed a significant technological trail. ... The public's response, according to those state supreme courts that provide those video broadcasts, border[ed] on the exuberant. . . [N]o state that currently provides video of its oral arguments cites grandstanding as a problem."

Arkansas has joined the majority of states that allow cameras in their courtrooms. There is simply no good reason for the Supreme Court not to do exactly the same thing.

A joke of a job interview

Summer Stories Wrap: U.S. Supreme Court

Summer Stories Wrap: U.S. Supreme Court Finally, we have to do something about the national farce that is our Supreme Court nomination process.

The sad spectacle of senators asking questions drafted by their staffs and then allowing the nominees to duck them should give way to serious conversations about the nominees' views so that the American people can participate more fully in the confirmation process. As almost everyone now knows, the justices have enormous discretion to decide cases in accordance with their personal and political value systems.

The differences between Justices Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg on most constitutional questions have nothing to do with legal interpretation and everything to do with their different backgrounds, experiences and values.

The Senate should do a much better job requiring nominees to answer hard questions about those values and experiences before the nominees are allowed to sit on the highest court in the land.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Eric Segall.