- Back to Home »

- A shoe, and 1963 bombing

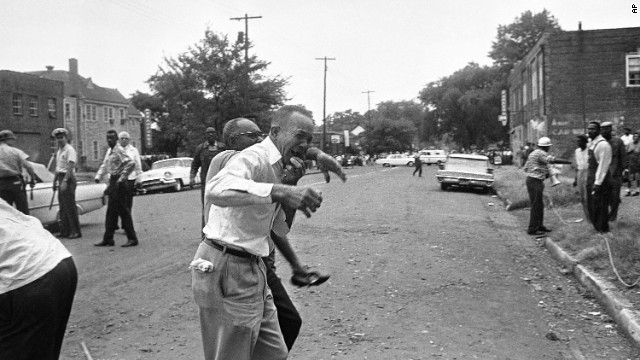

A grieving relative is led away from the site of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, on September 15, 1963. Four black girls were killed and at least 14 others were injured, sparking riots and a national outcry.

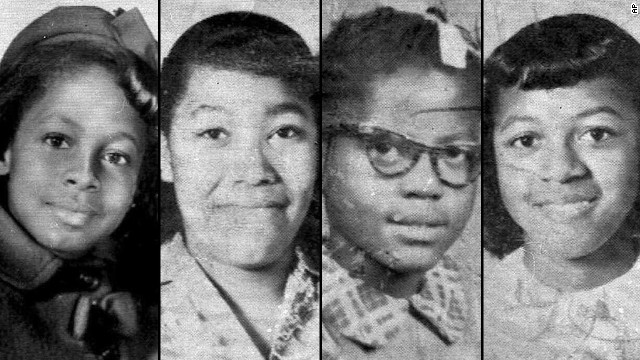

A grieving relative is led away from the site of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, on September 15, 1963. Four black girls were killed and at least 14 others were injured, sparking riots and a national outcry.  From left, 11-year-old Denise McNair and 14-year-olds Carole Robertson, Addie Mae Collins and Cynthia Wesley were killed while attending Sunday services. Three Ku Klux Klan members were later convicted of murder.

From left, 11-year-old Denise McNair and 14-year-olds Carole Robertson, Addie Mae Collins and Cynthia Wesley were killed while attending Sunday services. Three Ku Klux Klan members were later convicted of murder.  Firefighters and ambulance attendants remove a body from the church.

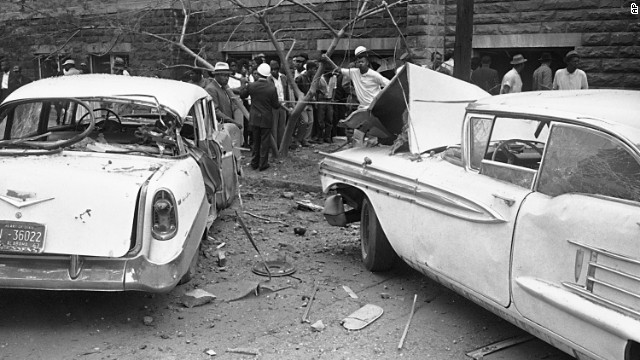

Firefighters and ambulance attendants remove a body from the church.  Cars parked beside the church were damaged by the blast.

Cars parked beside the church were damaged by the blast.  The 16th Street Baptist Church served as a rallying point during the civil rights movement. It was declared a national historic landmark in 2006.

The 16th Street Baptist Church served as a rallying point during the civil rights movement. It was declared a national historic landmark in 2006.  Sarah Jean Collins, 12, lost an eye in the blast. Her sister was one of the girls who died.

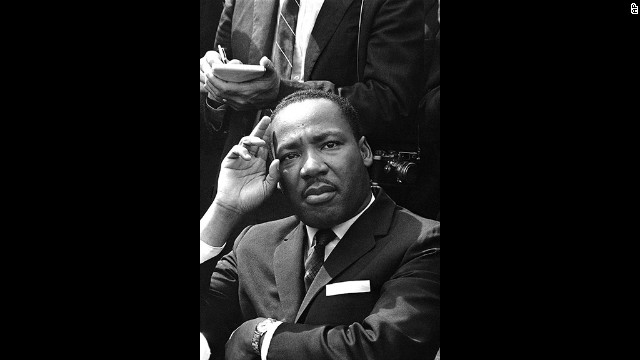

Sarah Jean Collins, 12, lost an eye in the blast. Her sister was one of the girls who died.  Martin Luther King Jr. holds a press conference in Birmingham the day after the attack. He said the U.S. Army "ought to come to Birmingham and take over this city and run it."

Martin Luther King Jr. holds a press conference in Birmingham the day after the attack. He said the U.S. Army "ought to come to Birmingham and take over this city and run it."  Family and friends of Carole Robertson attend graveside services for her in Birmingham on September 17, 1963.

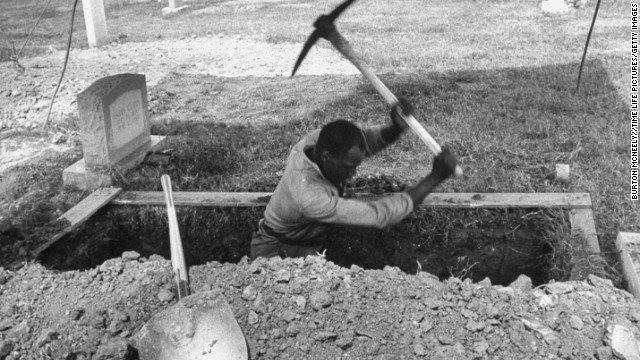

Family and friends of Carole Robertson attend graveside services for her in Birmingham on September 17, 1963.  A man digs a grave for one of the girls.

A man digs a grave for one of the girls.  A coffin is loaded into a hearse at a funeral for the girls. An estimated 8,000 people attended the service.

A coffin is loaded into a hearse at a funeral for the girls. An estimated 8,000 people attended the service.  Mourners embrace at the funeral. In his eulogy, Dr. King said, "These children -- unoffending, innocent and beautiful -- were the victims of one of the most vicious and tragic crimes ever perpetrated against humanity."

Mourners embrace at the funeral. In his eulogy, Dr. King said, "These children -- unoffending, innocent and beautiful -- were the victims of one of the most vicious and tragic crimes ever perpetrated against humanity." - Sept. 15 is the 50th anniversary of the Birmingham bombing that killed four children

- Roy Peter Clark recalls powerful column written by Atlanta Constitution editor Gene Patterson

- Patterson held the South's leaders to account for stoking an environment of hatred, he says

- Clark: Patterson was asked to read his column on newsman Walter Cronkite's show

Editor's note: Roy Peter Clark teaches writing at the Poynter Institute. He is the author of "Writing Tools" and the new book "How to Write Short: Word Craft for Fast Times." David Shedden contributed to the research for this article.

(CNN) -- On Sunday morning Sept. 15, 1963, a dynamite bomb exploded at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four black children, and injuring many others. The names of the dead girls were Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Denise McNair.

That afternoon a phone rang at the house of Gene Patterson, the editor of the Atlanta Constitution. Patterson was mowing the lawn, his nine-year-old daughter Mary nearby. The call from the office carried the horrible news from Birmingham. Patterson, without changing his clothes, drove to town and with tears in his eyes banged out a column so powerful that Walter Cronkite would ask him to read it for the CBS Evening News.

It began:

A Negro mother wept in the street Sunday morning in front of a Baptist Church in Birmingham. In her hand she held a shoe, one shoe, from the foot of her dead child. We hold that shoe with her.

Every one of us in the white South holds that small shoe in his hand.

It is too late to blame the sick criminals who handled the dynamite. The FBI and the police can deal with that kind. The charge against them is simple. They killed four children.

Only we can trace the truth, Southerner -- you and I. We broke those children's bodies.

T.S. Eliot once wrote that it is the job of the poet to find the sacred object that correlates to the emotion he wants to express. For Patterson, the object was that one small shoe:

We hold that shoe in our hand, Southerner. Let us see it straight, and look at the blood on it. Let us compare it with the unworthy speeches of Southern public men who have traduced the Negro; match it with the spectacle of shrilling children whose parents and teachers turned them free to spit epithets at small huddles of Negro school children for a week before this Sunday in Birmingham; hold up the shoe and look beyond it to the state house in Montgomery where the official attitudes of Alabama have been spoken in heat and anger.

Patterson's mentor Ralph McGill once criticized his own early editorials on issues of racial justice as "pale tea," and Patterson accepted the judgment for himself. Every day from 1960 to 1968, he wrote a signed editorial column in the paper, many of them devoted to issues of segregation and racial equality. As the years went by, his voice grew stronger.

In those more than 3,000 columns Patterson urged Southerners to do the right thing, to embrace Christian charity and common decency, to follow the law, promising that if they changed, "the sky would not fall."

"I see what you're doing," one reader accused. "You're trying to make us think we're better than we are."

On many days, Patterson's column expressed sympathy for the plight of the white Southerner and confidence that the South could change on its own, without the heavy hand of the federal government.

But not on September 15, 1963.

In a column that runs 553 words, Patterson uses the words 'we,' 'us,' and 'our,' more than twenty times:

Let us not lay the blame on some brutal fool who didn't know any better.

We know better. We created the day. We bear the judgment. May God have mercy on the poor South that has so been led. May what has happened hasten the day when the good South, which does live and has great being, will rise to this challenge of racial understanding and common humanity, and in the full power of its unasserted courage, assert itself.

The Sunday school play at Birmingham is ended. With a weeping Negro mother, we stand in the bitter smoke and hold a shoe. If our South is ever to be what we wish it to be, we will plant a flower of nobler resolve for the South now upon these four small graves that we dug.

It is almost unimaginable today that a columnist would be asked to read his work on the evening network news, but that's what happened to Patterson when CBS and Cronkite called. (Recordings of that show have not survived.) The broadcast carried the message of that one small shoe around the nation. Patterson received more than 2,000 letters in response.

Patterson would go on to win a Pulitzer Prize in 1967 for his editorial columns on racial justice. He briefly served as managing editor of the Washington Post, taught at Duke University, and became editor of the St. Petersburg Times (now the Tampa Bay Times) and chairman of the Poynter Institute, the school for journalism and democracy where I have worked since 1979.

Patterson hired me to teach writing there and became my friend and mentor until his death earlier this year at the age of 89. The library at Poynter is named after him. His photo hangs there, not far from a calligraphed rendition of his famous editorial.

It is part of an artistic work by the late African American artist John Scott called "I Remember Birmingham," comprising four glass cubes, each one representing one of the dead girls. Words etched on the glass are intended to be "heard" as the lost voices of the victims. The translucent cubes remind us of the stained-glass shattered in the bombings. (Three former members of the Ku Klux Klan were eventually convicted of murder for the bombings; one survives, in prison.)

This may be the 50th anniversary of their deaths, but I think of those four girls every day of my working life.

Patterson never took credit for his progressive views on race. He knew what he was doing was dangerous. A ball peen hammer in a desk drawer not far from his typewriter was there for any Klansman who might wander in. "I never had to use it," he told me, "but I pulled out the drawer a couple of times." He repeated again and again that the heroes of that era were black civil rights workers who put their lives on the line every day to dismantle America's version of apartheid, men and women such as Rep. John Lewis.

I met Lewis at a tribute for Patterson held in 2002 at Gene's old newspaper in Atlanta. Patterson, who had been a tank commander in Patton's army, was an emotional man who could almost never bring himself to read his old work aloud, so I read "A Flower for the Graves" to a group of assembled admirers. "I remember reading it back then," Rep. Lewis told me. "I had tears in my eyes."

In 2003 Patterson did a radio interview with WUNC in North Carolina. Host Frank Stasio asked Gene to read the column on the air, and he did so reluctantly, but only a couple of passages, his voice rising like a preacher when he came to the phrase "one shoe."

"God, Gene, you still sound angry," said Stacio.

Patterson responded, his voice catching, "About that -- yeah."

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Roy Peter Clark.