- Back to Home »

- Can cassette tapes be cool again?

Today is Cassette Store Day, which its organizers hope will attract you back to the format popular in the '70s and '80s. Sure, it had its frustrations -- unspooling or twisting tape, occasionally muffled sound -- but there was also the mix tape, staple of budding romances,and now a culty coolness as bands like the Flaming Lips and Grape Soda issue their music on cassettes.

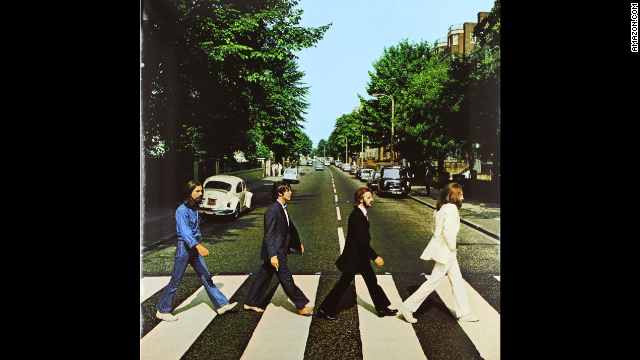

Today is Cassette Store Day, which its organizers hope will attract you back to the format popular in the '70s and '80s. Sure, it had its frustrations -- unspooling or twisting tape, occasionally muffled sound -- but there was also the mix tape, staple of budding romances,and now a culty coolness as bands like the Flaming Lips and Grape Soda issue their music on cassettes.  Like cassettes, vinyl records offer tactile pleasure and better sound and dominated music sales before cassettes-- and then CDs and MP3 files --came along. But even old vinyl has continued to sell, helped by a new surge in fondness for the format. The Beatles' "Abbey Road," for example, was the top-selling record in 2010 and 2011.

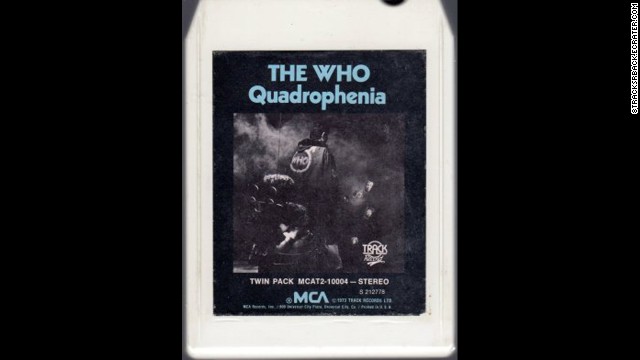

Like cassettes, vinyl records offer tactile pleasure and better sound and dominated music sales before cassettes-- and then CDs and MP3 files --came along. But even old vinyl has continued to sell, helped by a new surge in fondness for the format. The Beatles' "Abbey Road," for example, was the top-selling record in 2010 and 2011.  Hard to imagine, but there was a time everyone thought they wanted clunky 8-track cassettes. In the '60s, Ford started putting 8-track tape decks in its cars, and soon, sales of this format left cassettes in the dust. But this was bound to end ...

Hard to imagine, but there was a time everyone thought they wanted clunky 8-track cassettes. In the '60s, Ford started putting 8-track tape decks in its cars, and soon, sales of this format left cassettes in the dust. But this was bound to end ...  With the arrival of the boom box, cassettes came back into vogue in the '80s. This hulking music delivery system was considered "portable" and helped propel cassette sales.

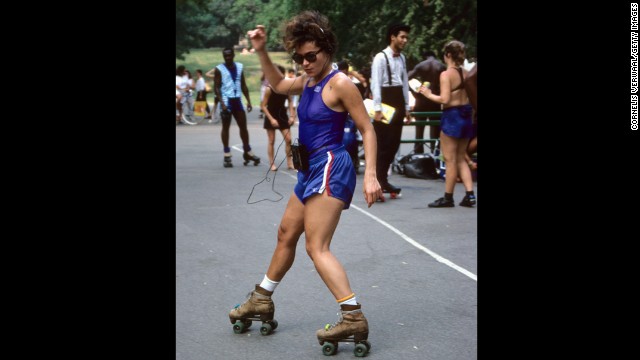

With the arrival of the boom box, cassettes came back into vogue in the '80s. This hulking music delivery system was considered "portable" and helped propel cassette sales.  The Walkman made listening to music truly portable -- and personal -- and in the '80s helped cassette sales outstrip vinyl for the first time. The ability to record one's own tapes was always a huge part of the cassette's appeal.

The Walkman made listening to music truly portable -- and personal -- and in the '80s helped cassette sales outstrip vinyl for the first time. The ability to record one's own tapes was always a huge part of the cassette's appeal.  Cassettes and LPs faded from the scene in the early '90s, when compact discs appeared and music went digital.

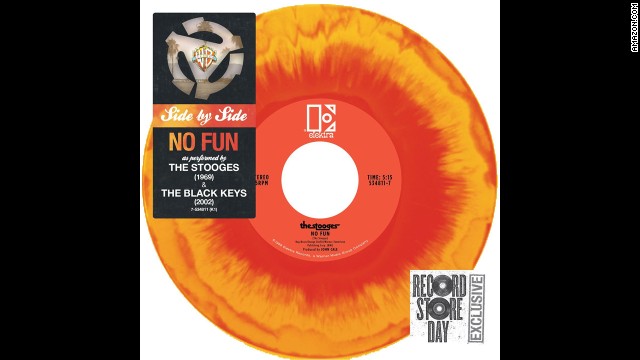

Cassettes and LPs faded from the scene in the early '90s, when compact discs appeared and music went digital.  But vinyl has returned on a wave of hipster chic and nostalgia, not to mention audiophiles' conviction that records just sound better. Most new releases today -- like this double-sided record from the Stooges and the Black Keys -- come out in vinyl, too.

But vinyl has returned on a wave of hipster chic and nostalgia, not to mention audiophiles' conviction that records just sound better. Most new releases today -- like this double-sided record from the Stooges and the Black Keys -- come out in vinyl, too.  An increasing number of bands, such as MGMT, have released new music on cassette, and Cassette Store Day organizers promise release of a Fair Ohs double cassette and a Los Campesinos! live album on tape, among others. Can the trend catch up to vinyl's resurgence? It's still early.

An increasing number of bands, such as MGMT, have released new music on cassette, and Cassette Store Day organizers promise release of a Fair Ohs double cassette and a Los Campesinos! live album on tape, among others. Can the trend catch up to vinyl's resurgence? It's still early.  Listening to music is largely about MP3s now, but, says Mark Coleman, something unique -- personal -- was left behind in the move to digital. "If you dust off those outmoded physical formats like cassette tapes and vinyl records down in the basement, they produce more than memories: They play music."

Listening to music is largely about MP3s now, but, says Mark Coleman, something unique -- personal -- was left behind in the move to digital. "If you dust off those outmoded physical formats like cassette tapes and vinyl records down in the basement, they produce more than memories: They play music." - Mark Coleman: It's Cassette Store Day. Why would we celebrate this? Let's play along

- Organizers want to stimulate a resurgence of cassette tapes, first sold in the '60s, he says

- He says cassette tapes warred with vinyl and 8-track tapes for dominance, sometimes winning

- Coleman: Their quality improved, though they fell from favor. But still a cultural touchstone

Editor's note: Mark Coleman is the author of "Playback: From the Victrola to MP3, 100 Years of Music, Machines and Money."

(CNN) -- The cassette tape is back! Or at least this is what the organizers of Cassette Store Day -- that's right, it's today -- would have us believe. Cassettes? Really? Let's play along, if only for nostalgia's sake.

Fifty years after the prototype cassette was introduced at the 1963 Berlin Radio Show, a group of independent labels that release new cassettes have pulled together the global event celebrating and, they hope, stimulating the resurgence of prerecorded tapes.

The day will be observed, according to the group's website, at roughly 100 retail stores and music venues in the U.S., Europe, Canada and South America, with tie-ins, new cassette releases and live performers pushing new tapes. Cassette releases from established bands like At the Drive-In and Flaming Lips will be vended, as well as tapes from underground artists like Grape Soda and Gold Bears on the Hope for the Tape Deck label.

Anyone who remembers fumbling with a cassette deck while driving or listening as a tape unspooled and self-destructed in the tape deck or having to insert index finger or pen into the cassette in a usually vain attempt to rewind the hopelessly twisted tape must be asking a simple question: Why?

In the seamless age of digital music, when seemingly every song ever recorded is available at the stroke of a few computer keys, why would anyone revive such a clunky and outmoded physical format?

But consider: Even with the convenience and sheer abundance of music stored on MP3 files, cassettes (and vinyl) offer tangible and tactile pleasures that aren't readily available in the digital world. There's a sizable, and growing, subset of consumers who lust for musical objects that they can hold in their hands (and their hearts) as well as their ears.

"Metal and punk and noise people never stopped releasing cassettes," says Scott Seward. He is a music critic and owner of John Doe Jr. Used Records and Books in Greenfield, Massachusetts. "Fans of that music have always collected tapes. Same with jam band and Grateful Dead fans until recent years. It's still a common format for a lot of Middle Eastern, Indian and Asian street or folk music too, because cassettes are so cheap to reproduce."

It's true. Cassettes have always been an alternative and were for many years something of an underdog in the musical format wars. Not long after prerecorded cassettes emerged in the vinyl-dominated marketplace, the 8-track tape format eclipsed them in popularity. That was largely because the Ford Motor Co. started offering 8-track players as an option on some of its cars beginning in 1966.

The automobile would power sales of the 8-track format past the cassette in the music-mad '60s and '70s. Drivers could insert and remove the bulky 8-tracks with one hand. By 1975, incredibly, 8-track tapes were second only to vinyl records in terms of sales figures.

Cassettes had already been a tough sell to audiophiles because until the advent of Dolby noise reduction in the '70s, their sound quality was muffled compared with vinyl records. Gradually that improved, just as new tape playback options emerged.

Even before the Walkman, the portable stereos known as boom boxes boosted the popularity of cassettes in the urban areas where these hulking radio/tape players (aka ghetto blasters) were most often used. Boom boxes made music consumption a public event (often whether the public wanted it or not) while advancing the notion of portability.

But consumers began to demand portable music players. In late 1979, Sony introduced the proto-Walkman. Retailing for $199, the Soundabout was a 14-ounce playback-only device that came with headphones and used standard-size cassettes. By 1981, the smaller and cheaper Walkman II was available.

When it comes to recorded music formats, portable equals personal. So it's no accident that the Walkman and similar devices became known as personal stereos in the early '80s. Soon, Walkman headphones were as ubiquitous as boom boxes on city streets.

Thanks to the Walkman, the boom box and the cassette (and later the CD), sales of vinyl records plummeted during the '80s. In 1981, more than twice as many vinyl records as prerecorded cassettes were sold. By 1984, the numbers had flipped, and cassette sales outpaced vinyl for the first time.

Despite the unsuccessful "Home Taping Is Killing Music" campaign of the early '80s, the ability to record one's own tapes was always a huge part of the cassette's appeal. Homemade mix tapes became a cultural touchstone for a generation (or two), functioning as diaries or journals and figuring in courtship rituals (see Rob Sheffield's affecting memoir "Love Is A Mix Tape"). When cassettes faded from the scene in the early '90s in the conquering wake of the CD, something unique -- personal -- got left behind.

Gone, perhaps, but not forgotten. The pull of nostalgia is not the only motivation behind the recent cassette cult resurgence, but memories and recorded music are deeply -- some say neurologically -- intertwined.

"There is that True Cult aspect," Seward says. "It's an exclusivity thing. Cassettes just seem like a cooler thing to have for sale at your punk or noise show than a CDR. Black metal and power electronics sound fab on tape, though. Same with Miami bass music. I still listen to a lot of metal and rap on tape, and I make mix tapes from vinyl that sound amazing."

Even if Cassette Store Day fails to bring prerecorded cassettes back to commercial prominence, the event makes a telling point about our music consumption. Despite the digital revolution, if you dust off those outmoded physical formats like cassette tapes and vinyl records down in the basement, they produce more than memories: They play music. They still work. Their appeal, however sentimental, is stronger than mere nostalgia.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Mark Coleman.