- Back to Home »

- The new Franciscan revolution

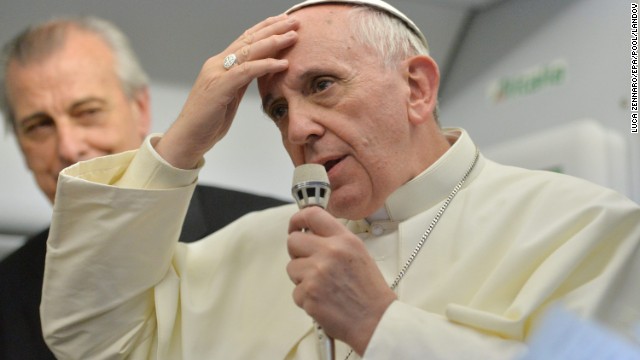

Pope Francis makes some unexpected comments on issues facing the Roman Catholic Church on Monday, July 29. He spoke on the record to journalists on a flight back back to Italy from Brazil after finishing his first international trip as pontiff. Among the topics he addressed were homosexuality, the church's alleged "gay lobby," the role of women, abortion, divorce and the Vatican Bank.

Pope Francis makes some unexpected comments on issues facing the Roman Catholic Church on Monday, July 29. He spoke on the record to journalists on a flight back back to Italy from Brazil after finishing his first international trip as pontiff. Among the topics he addressed were homosexuality, the church's alleged "gay lobby," the role of women, abortion, divorce and the Vatican Bank.  On the flight, Francis said he will not "judge" gay priests, a huge shift from his predecessor, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, who sought to bar men with "homosexual tendencies." "If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?" Francis said.

On the flight, Francis said he will not "judge" gay priests, a huge shift from his predecessor, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, who sought to bar men with "homosexual tendencies." "If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?" Francis said.  A journalist takes a picture of Pope Francis during the press conference on the flight back to Italy. The pope said the role of women in the church should be deeper, but he brushed aside the possibility of women being ordained as priests. "The church says no. That door is closed."

A journalist takes a picture of Pope Francis during the press conference on the flight back to Italy. The pope said the role of women in the church should be deeper, but he brushed aside the possibility of women being ordained as priests. "The church says no. That door is closed."  Francis said he had nothing to say about abortion while in Brazil because church teachings against it were clear and his trip was the time for "positive" news.

Francis said he had nothing to say about abortion while in Brazil because church teachings against it were clear and his trip was the time for "positive" news.  Pope Francis sits inside the plane at a Rio de Janeiro air base Sunday, July 28, before departing for Rome. On the trip back, the pope said cardinals were exploring the question of whether divorced people can receive communion, which they are currently banned from doing. He also said he was unsure what to do with the Vatican Bank, which has faced corruption allegations recently.

Pope Francis sits inside the plane at a Rio de Janeiro air base Sunday, July 28, before departing for Rome. On the trip back, the pope said cardinals were exploring the question of whether divorced people can receive communion, which they are currently banned from doing. He also said he was unsure what to do with the Vatican Bank, which has faced corruption allegations recently. - David Perry: Pope Francis has not called for any new doctrines or changed anything

- Perry: Francis' impact comes from his behavior and words, not his executive power as Pope

- He says that the pope can seem so transformative is a testament to the power of his reform

- Perry: When will the rest of the Catholic Church hierarchy catch up to Francis' revolution?

Editor's note: David M. Perry is an associate professor of history and director of the Catholic studies minor at Dominican University in Illinois. Follow him on Twitter.

(CNN) -- It's time to stop being surprised by Pope Francis.

Since he became pontiff, he's made a lot of news. His tweets echo around the world. He embodies principles of humility and piety. He eschews the fancy trappings of office favored by his predecessor, from the Popemobile to the red shoes. He washed the feet of prisoners, including a Muslim woman, on Holy Thursday. He telephones ordinary people who write to him.

In Rome, he called for "revolutionaries" to leave the comforts of their home and bring the word into the streets. In Rio, he told the gathered youth to "make a mess" in the dioceses as they help the church shake off clericalism.

He has sought to create a "culture of encounter" in which atheists and Catholics might come together. "Do good," he said memorably. "We will meet each other there." When he announced that he would canonize Pope John XXIII, the great reformer, on the same day as John Paul II, he emphasized continuity among all Catholics, even those of different factions. When asked about gay priests, he replied, "Who am I to judge?"

Most recently, he gave a long interview in which he articulated a new vision of the church that does seem revolutionary. In the West, reaction has focused on his statements about hot-button social issues. For example, he said, "the teaching of the church (on abortion, gay marriage, and contraception), for that matter, is clear ... (but) it is not necessary to talk about these issues all the time."

Given the constant drumbeat of the American church hierarchy on exactly those issues, the line comes off as a surprising rebuke. Deeper critiques lie within the interview as well. When he spoke about doubt and dialogue, he said, "If the Christian is a restorationist, a legalist, if he wants everything clear and safe, then he will find nothing."

At the very least, Francis has found a message that resonates with Catholics and non-Catholics alike. But as repeatedly stated by commentators and church officials, he has not changed anything. He has called for no new doctrines. His reorganization of the Vatican goes slowly. The problems besetting the church before his election remain. Traditionalists, who wish to preserve gains won under the past two popes, and reformers, who are frustrated by the pace of change, agree on this one thing. To this point, Francis' impact emerges from his behavior and his words, not his executive power as pope.

New pope, new path?

New pope, new path?  Pope Francis' views a 'slight departure'

Pope Francis' views a 'slight departure'  What is Pope Francis' message?

What is Pope Francis' message? And yet, he has this power to surprise. Every time he demonstrates his humility or his empathy, his words resonate with Catholics and non-Catholics alike. They bring both pleasure and surprise that such a seemingly honest, humble and holy person really could be pope.

Don't be surprised at what Francis is doing; instead, wonder if the rest of the church hierarchy is going to catch up. Francis' revolution emerges out of the core of Catholicism. He emphasizes humility, poverty, social justice, non-judgment, peace and especially mercy. That he can seem so transformative without changing any theological principles is a testament to the depth and power of his reform, not its limitations.

Such a reform has historical precedent. More than 800 years ago, another Francis, the son of a cloth merchant in Assisi, came to Rome to see the pope. The church of the 13th century relied heavily on ritual and formula. This reliance distanced the priests from their parishioners and was a growing problem in an era of societal change. Francis and his disciples, who attempted to live in perfect poverty and humility, had dedicated themselves to preaching and outreach to the people. They tried to pattern their lives by the principles of Christ.

The pope, Innocent III, gave Francis his approval and supported the new Franciscan order. He hoped that the charismatic humility of Francis might help address some of the problems the church was facing. Eight hundred years later, Archbishop Jorge Bergoglio became the first pope to take Francis' name as his own.

St. Francis' revolutionary message focused on a return to first principles, as he saw them. While Pope Francis has ascended to the throne of St. Peter and St. Francis never chose to be ordained, one can locate certain parallels unfolding between the two men and their efforts at reform. This pope is also turning to the first principles as he perceives them. Pope Francis makes the argument that everything he needs to transform the church already exists within the core teachings. And if this is the core, how can anyone choose not to follow?

What would it look like for the rest of the hierarchy to go where Francis is leading? For one thing, they might find lots of their lay parishioners and the women and men in holy order already there, working.

But while the hierarchy clearly elected Francis to reform the workings of the Vatican, it's not clear that they expected his personal piety to put such pressure on them. Traditionalist response to Francis has concentrated on his personal charisma while emphasizing the orthodoxy of his doctrinal positions. Such responses seem to indicate a resistance to the idea that they might need to change anything.

In a recent interview with the New Catholic Reporter, Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York talked about the new pope. He said that in the wake of Francis, he found himself "examining my own conscience ... on style, on simplicity, on lots of things." The cardinal wondered whether his living arrangements, in the historical residence of the archbishops of New York, were appropriate. But the cardinal wasn't quite sure what to do about it, given that he can't sell the building.

St. Francis would have agreed. He carefully never argued for the church to sell of its property or divest itself of income. Of course, he was outside the church hierarchy and relied on papal protection for his safety.

Pope Francis, on the other hand, might have a plan for an empty archbishop's residence if Cardinal Dolan wanted to downsize. After all, he did recently suggest that empty church property should be used to house refugees.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of David Perry.