- Back to Home »

- The year that changed the world

- This week marks the anniversary of the unveiling of the U.S. Constitution in 1787

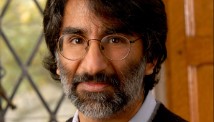

- Akhil Amar: Over the following 12 months, America debated the ground rules for a new kind of democracy

- On voting rights, the U.S. has recently taken backward steps; free speech is flourishing, he says

- Amar: Constitutional self-government rules half the globe, thanks to U.S. example

Editor's note: Akhil Reed Amar is Sterling Professor of Law and Political Science at Yale, and the author of "America's Unwritten Constitution: The Precedents and Principles We Live By." (2012). This piece was written in association with the Robert H. Smith Center for the Constitution.

(CNN) -- This week we mark Constitution Day, commemorating the electrifying moment on September 17, 1787 when the Philadelphia framers went public with their proposed Constitution.

Over the ensuing year, Americans debated and ratified this audacious plan, and thereby gave birth to a far better world. Let's recall the central features of that year that changed everything so that we can measure how far we have come, and how far we still need to go, to redeem the Constitution's promise.

After its public unveiling in mid-September, the Philadelphia plan was put to a vote across the continent, in a process that let vastly more ordinary folk than ever before in human history decide how they would be governed.

In most states, standard property qualifications were lowered or eliminated for this special ratification election. New York, for the first time in its history, let all adult free male citizens vote -- no property qualifications, no race tests, no religious qualifications, no literacy tests -- for ratifying-convention delegates who in turn voted yes on the Constitution several months later.

Later generations have nobly built upon this foundation, repeatedly adding the words "the right to vote" in a grand colonnade of amendments promising a permanent end to all sorts of electoral discrimination and exclusions. That's undeniable progress.

But America no longer leads the world in the integrity and inclusiveness of our elections; several states are now shamelessly trying to roll back voting rights; the Supreme Court has renounced a key piece of the landmark Voting Rights Act; and Congress has yet to mend the tattered statute.

Modern American free speech is a happier story, with robust free expression in almost every corner of the land. Here, too, we have 1787-88 to thank, a year when Americans dramatically embodied free speech in the very process of establishing the Constitution. No one was censored that year, and the document's opponents were not forever demonized or voted off the island.

In fact, several of the Constitution's early critics came to rank among the new nation's highest leaders -- for example, President James Monroe, Vice Presidents George Clinton and Elbridge Gerry, and Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase.

The two camps that had sharply divided over the Constitution's ratification -- the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists -- soon thereafter found common ground in supporting a Bill of Rights. Is it too much to hope that today's polarized parties might learn something from this inspiring example, and try to find something -- anything! -- that they can agree upon?

Perhaps because the Constitution's supporters did not try to muzzle skeptics, these skeptics, when outvoted, acquiesced. In several states, the document squeaked through only by the narrowest of margins -- for example, 30 to 27 in New York.

Yet everyone accepted the basic principle of majority rule, even though the document itself did not explicitly specify this voting rule. Here, too, there are lessons for today.

The entrenched filibuster has made the current Senate a deeply dysfunctional body, yet some senators seem to think that a supermajority-rule system has deep roots in founding principles and practices. These senators are mistaken.

The early Senate followed the principles of 1787-88, and the key principle that year in every single state ratifying convention was simple majority rule. Everyone got to speak; and then votes ensued, and simple majorities prevailed. Period.

Finally, let's note the extraordinary religious inclusion championed by the document first unveiled in mid-September 1787. Unlike most revolutionary state constitutions and the contemporaneous rules generally in place elsewhere on the planet, the Constitution opened its doors to office seekers of all faiths and philosophies.

Last year, three of the four men atop the major party tickets -- Mitt Romney, Paul Ryan, and Joe Biden -- were not members of the mainstream Protestant churches that dominated society at the founding. Today's speaker of the House is a Catholic, the Senate majority leader is a Mormon, and no Protestant sits on the current U.S. Supreme Court.

One is tempted to say, "only in America!" but in fact there are other modern countries that are democratic and religiously pluralist. However, many of these democracies have been powerfully influenced by the American constitutional experience.

Before the Constitution went public in 1787, pluralistic democracy existed almost nowhere on the planet, outside America. Thus it had always been throughout recorded history. Today, constitutional self-government reigns across half the globe, and it does so thanks largely to the legal, political, cultural, moral and military success of the American constitutional project.

In short, the world is becoming more American (and America itself, thanks to trade and immigration, is becoming more global). So we should not say "only in America," but rather "only because of America" -- and in particular, because of America's Constitution and because of the year that changed everything.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Akhil Amar.