- Back to Home »

- Where America became exceptional

- Simon Winchester: America's military patrols the world, unlike that of any other nation

- He says the belief in American exceptionalism goes back to the frontier days

- Americans saw themselves as tamers of an uncharted, untamed wilderness, he says

- Winchester: Vladimir Putin could learn a lot about exceptionalism if he studied U.S. history

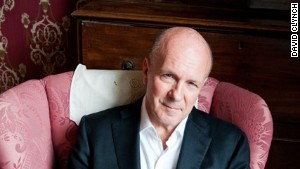

Editor's note: Simon Winchester, born in London in 1944 and awarded the officership of the Order of the British Empire, OBE, by Queen Elizabeth II in 2006, became a U.S. citizen in a ceremony aboard the USS Constitution in Boston Harbor on July 4, 2011. His most recent book, "The Men Who United the States", will be published by HarperCollins on October 15. He spoke at an event organized by TEDx East in August. TED is a nonprofit dedicated to "Ideas worth spreading".

(CNN) -- Once in a while, along a steady reach of the wide Missouri River some 70 miles east of Kansas City, the local corn farmers will pause in their labors for a huge rumbling sound, a thunder of jet engines shaking the willows and cottonwoods and the gliding stillness of the stream.

Moments later, from behind long razor-wire fences, and rising from an invisible runway folded among the cornfields, a great gray bomber will slowly lumber upwards and hoist itself up into the skies.

It is always an awesome sight -- all the more so if other planes follow, and the singleton becomes part of an airborne armada, a squadron of unimaginable power bound on an unannounced mission to a place seldom disclosed, for a purpose rarely to be known.

And as the craft vanish into the clouds, and the thunder ebbs away over the woods, so the awestruck locals must wonder: Just what corner of the planet is this day destined to be basking under the unasked-for invigilation of these nuclear-tipped watchers from America's skies.

For this, in the trails of burned jet fuel scarring the Midwestern skies, is a closeup of the face of today's American exceptionalism.

The bombers come from Whiteman Air Force Base, home to the unit that once bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki, an always battle-ready line of B-2 stealth aircraft that its commander proudly says can now deliver massive firepower to bear, in a short time, anywhere on the globe.

The crews sent two planes to Korea last spring to warn the saber-rattling North Korea dictator to keep in line. They currently stand armed and ready to deploy a squadron to Syria, should their commander-in-chief issue the order. And should they be told to fly to China, or to Kosovo again, or to Congo, so they will unpack their charts and load their bombs and cannons and rumble off down the Whiteman runways.

They are the outward manifestation of the still closely held belief that America, unique in all the world, has a prescriptive right to send weapons of unrivaled might to any place on the surface of the planet, to make sure inhabitants there behave themselves, and march steadily to a tune conducted by the United States.

But -- why? This, essentially, was what Vladimir Putin was asking in his now-infamous New York Times op-ed essay. Just why does America still believe that it has a right and a duty to police the world? Why does America consider itself so different -- so sufficiently exceptional as to have a perpetual duty of care for all major happenings around the globe?

Simon Winchester

Without excusing this reality, I would argue that this idea was actually born, two centuries ago, in places just like the far west of Missouri, just where the Whiteman base is hidden. It is a geographical irony based on the existence in such places of a phenomenon long since vanished: the frontier.

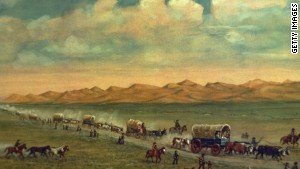

When Lewis and Clark passed by -- and just near where the base is now, Lewis wrote in 1804 of having seen "an emence snake...that gobbles like a turkey" -- this was very much the frontier. Behind the men, back east, were the beginnings of civilization: towns, roads, governments, the law.

Ahead was uncharted and untamed wilderness. Behind were traders, farmers, settlers, surveyors; beyond were empty prairies, nomads, lawlessness. And according to some this vague frontier line, shifting ever westward for much of the next century as the nation was opened up, instilled something unique in the American character.

A Wisconsin history professor named Frederick Jackson Turner first advanced the idea: that those tested by the frontier experience were a people more violent, more informal, more democratic, more imbued with personal initiative and less hamstrung by tradition, class and elegance. More American, Turner suggested.

Strength, power, might -- the ability to tame rather than to persuade, the tendency to demand rather than request, the tendency to shoot rather than to talk -- these were all tendencies compounded by the frontier experience, uniquely different building-blocks employed the making of the modern American.

The Western myth, the legends of the cowboy, the cinematic and entertainment park allure of concepts like Frontierland -- all of these were born from this single simple -- some would say simplistic -- thesis offered up by Frederick Jackson Turner.

Since then the theory has been much derided -- Turner, it is argued, paid no heed to such matters as race, gender and regionalism. And yet it seems to me much of what he argued still does have a measure of common sense to it.

For Americans are different: The notions of Manifest Destiny and the vision of America as the shining city on the hill, surely do owe something at least to the frontier mentality. And I would argue that this mentality, if such a thing exists, still also plays a nourishing role at the intellectual roots of much of today's American foreign policy.

There is much more to it, of course. American foreign policy may well be driven nowadays more by corporate greed than by a frontier-tested belief in noble ideals. But Vladimir Putin, by learning a little more about this country's remarkable past, might also come to have a more sympathetic understanding about why it is the nature of Americans to believe they are truly unusual, with a unique role to play in the world, and to have little patience with those who wish it were otherwise.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter.

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Simon Winchester.